Begin typing your search above and press return to search.

Law in Sports

India closer to egalitarian play: A look at women in sports

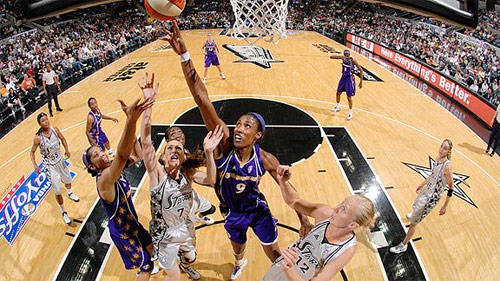

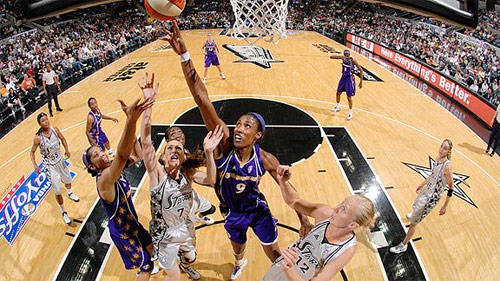

This article first appeared on KhelAdhikar, written by Wilfred Synrem, the Chief Editor at KhelAdhikar (3rd Year Student at Gujarat National Law University). He can be reached at [email protected] --------- “Women get the attention when we get into the men’s arena, and that’s sad.” As controversial it can be, these striking words of the famous Billie Jean King not only emphasised upon the status of women’s tennis in the 1970’s but also resounds with the current situation of women sports. And, if one would contemplate on those words for its true meaning, there would be a handful of interpretations; all of which reflect one terminology, ‘Gender Discrimination’. Gender discrimination in Sports itself can be witnessed in various forms such as the gender pay gap between the male and female athletes, the sexist attitude towards female sportspersons or even sexual harassment incidents. No doubt facts and statistics endorse this discrimination, but the key to understanding the reasons for such inequality is essential. Coming back to Billie Jean King, she was one of the first few to advocate for equality by pushing for equal prize money. In 1973, the 39 Grand Slam title holder had founded a separate Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) in retort to her meagre U.S. Open prize money and shunned all taboos by beating Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes” game. As a result, the following edition of the U.S. Open had become the first ever major tournament to have offered equal prize money to women and men. But has a gender equality regime regarding daily wages and prize money been established in the current sports industries? In the Gender Inequality Issue of the Global Sports Salaries Survey, 2017, it was duly noted that the gender pay gap in Sport is more than in politics, business, medicine or even academia. Currently, on an average, a male basketball athlete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) earns $7,147,217 which is equivalent to ninety-six times the salaries of their female counterparts.  Currently, on an average, a male basketball athlete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) earns the equivalent of ninety-six times the salaries of their female counterparts. This disparity speaks volumes especially when you consider the fact that the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is highest paid women’s league in the World. Another illustration can be seen in the ongoing FIFA Men’s World Cup, wherein the prize money is set at 400 million dollars compared to the 15-million-dollar prize for the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Similarly, the average earners of the English Premier League get paid 100 times more than the women in the equivalent FA Women’s Super League. And finally, to top it all, the Forbes 2018 Highest Paid Athletes does not include a single sportswoman within its top 100.

Currently, on an average, a male basketball athlete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) earns the equivalent of ninety-six times the salaries of their female counterparts. This disparity speaks volumes especially when you consider the fact that the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is highest paid women’s league in the World. Another illustration can be seen in the ongoing FIFA Men’s World Cup, wherein the prize money is set at 400 million dollars compared to the 15-million-dollar prize for the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Similarly, the average earners of the English Premier League get paid 100 times more than the women in the equivalent FA Women’s Super League. And finally, to top it all, the Forbes 2018 Highest Paid Athletes does not include a single sportswoman within its top 100.

Also read: The curious case of discrimination in sports earnings

BCCI’s 2018 retainer contracts for its senior men and women players exemplified the same, where the highest earners, i.e. ‘A’ grade women cricketers (Rs.50 L) receive half the pay of the ‘C’ grade lowest earning men cricketers (Rs.1Cr). Also, the men’s team have been offered a salary of 7 crores per annum for cricketers of the ‘A+’ grade or ‘top performers’, leaving behind no such classification for the women’s team. The women of the Indian Football team despite their current World ranking of 59 earn between five to ten lakh rupees, while the men’s team draw around 70 lakhs per year. And yes, the pinnacle sport of India, ‘Hockey’ also has a ten-fold wage gap between both its teams.

BCCI’s 2018 retainer contracts for its senior men and women players exemplified the same, where the highest earners, i.e. ‘A’ grade women cricketers (Rs.50 L) receive half the pay of the ‘C’ grade lowest earning men cricketers (Rs.1Cr). Also, the men’s team have been offered a salary of 7 crores per annum for cricketers of the ‘A+’ grade or ‘top performers’, leaving behind no such classification for the women’s team. The women of the Indian Football team despite their current World ranking of 59 earn between five to ten lakh rupees, while the men’s team draw around 70 lakhs per year. And yes, the pinnacle sport of India, ‘Hockey’ also has a ten-fold wage gap between both its teams.  The Sports Authority of India had ignored Dipa Karmakar’s request for her physiotherapist before her vault finals in the Rio Olympics. Incentive wise, one must look at the prestigious awards dished out by the Government towards its Indian athletes since time immemorial. Because the women sportspersons have been as successful as the male contingent for India, the former only accruing for one-fourth of the overall Arjuna awards reminds us of the gender-biased accolades in India. In toto, gender discrimination is widespread and prevalent in India and multiple other countries. Ranging from sexist posters implemented for cycling races to the FIFA World Cup (Women) being played on artificial turf (compared to the grass field used for the men’s tournament which reduces injury threats), the gender bias situation is nothing short of sad.

The Sports Authority of India had ignored Dipa Karmakar’s request for her physiotherapist before her vault finals in the Rio Olympics. Incentive wise, one must look at the prestigious awards dished out by the Government towards its Indian athletes since time immemorial. Because the women sportspersons have been as successful as the male contingent for India, the former only accruing for one-fourth of the overall Arjuna awards reminds us of the gender-biased accolades in India. In toto, gender discrimination is widespread and prevalent in India and multiple other countries. Ranging from sexist posters implemented for cycling races to the FIFA World Cup (Women) being played on artificial turf (compared to the grass field used for the men’s tournament which reduces injury threats), the gender bias situation is nothing short of sad.  In its 2002 & 2003 editions, an Indian Sports weekly ‘Sportstar’ had ignored iconic sportswomen like Anju Bobby George (in 2003 she became the first ever Indian athlete to win a medal at the World Athletics Championship with a leap of 6.70 metres), Sania Mirza (first Indian woman to win a Grand Slam tennis title), and the Indian Hockey team (they had won Gold in the 2002 Commonwealth Games and the 2003 Afro-Asian Games) Not only is this argument rudimentary but also baseless. Just because of two reasons: One, comparing men’s sports and their abilities to women is like comparing apples with oranges. Two, men and women in games have not yet been placed on the same levelling ground for any sort of comparison, in the sense that women do not receive a similar kind of media coverage. Let me explain this vicious cycle. If female athletes do not receive sufficient media publicity, how can you expect a person to be inspired or interested in women’s sports especially when he or she has not witnessed the same on television or the news? Previously mentioned numbers endorse such a counter-argument. Further, if you integrate it with the remaining discriminatory elements which are likely to discourage the young girls, the sport would end up with fewer women. Less female sportspersons mean lesser publicity, i.e. smaller viewership revenue. Therefore, the cycle is never-ending because from every angle it can be seen that men and women have never been placed on an equal footing in the sports industry. Nonetheless, it is firmly believed that a more significant reason for the inequality is the lack of representation of women on boards of National Federations or Olympic Committees. A substantial majority of women on decision-making boards of such organisations can not only ensure an equitable distribution of federation funds but also vouch for the interests of women during policy decision making. According to a critical mass theory, a strong rather than mere representation of women on boards would bear significant fruit. The theory states that when a size of a group (here, women) reaches a critical mass or certain threshold, that group gains trust and influence (within the larger group, i.e. the whole board). Currently, four out of fifteen members of the IOC (International Olympic Committee) executive board are women (27%) and the percentage of women holding positions in the IOC Commissions are 38%. For the year 2015, the IOC had set a goal of having at least 20% women in all National Olympic Committees (NOC’s) out of which thirty-nine NOC’s had met the mark. Woefully, India’s NOC was in the bottom 10 with a shameful 3.57% of women representation. Research statistics reveal that out of all the National Sports Federations (NSF’s) in India, a staggering eight number of NSF’s {Swimming Federation of India, Volleyball Federation of India, India Rugby Union, etc.} were without any women representation and the remaining NSF’s women constituted 2% to 8% of the governing bodies {Hockey had the highest representation at 34%}. Although India’s National Sports Development Code (2011) supports the protection of gender equality in sports, neither the Code nor any other policy stipulates any minimum percentage for women representation on NSF or NOC boards. Therefore, there should be an onus on Indian Sports Associations to improve the disparity on their governing boards, just like other international countries. India can learn from the United Kingdom’s Code for Sports Governance (2017) wherein Principle 2.1 requires each organization to ensure a minimum of 30% of each gender on its governing board. The intent of this principle is not only to maintain gender parity but also to facilitate open-ended board discussions from both ends of the spectrum.

In its 2002 & 2003 editions, an Indian Sports weekly ‘Sportstar’ had ignored iconic sportswomen like Anju Bobby George (in 2003 she became the first ever Indian athlete to win a medal at the World Athletics Championship with a leap of 6.70 metres), Sania Mirza (first Indian woman to win a Grand Slam tennis title), and the Indian Hockey team (they had won Gold in the 2002 Commonwealth Games and the 2003 Afro-Asian Games) Not only is this argument rudimentary but also baseless. Just because of two reasons: One, comparing men’s sports and their abilities to women is like comparing apples with oranges. Two, men and women in games have not yet been placed on the same levelling ground for any sort of comparison, in the sense that women do not receive a similar kind of media coverage. Let me explain this vicious cycle. If female athletes do not receive sufficient media publicity, how can you expect a person to be inspired or interested in women’s sports especially when he or she has not witnessed the same on television or the news? Previously mentioned numbers endorse such a counter-argument. Further, if you integrate it with the remaining discriminatory elements which are likely to discourage the young girls, the sport would end up with fewer women. Less female sportspersons mean lesser publicity, i.e. smaller viewership revenue. Therefore, the cycle is never-ending because from every angle it can be seen that men and women have never been placed on an equal footing in the sports industry. Nonetheless, it is firmly believed that a more significant reason for the inequality is the lack of representation of women on boards of National Federations or Olympic Committees. A substantial majority of women on decision-making boards of such organisations can not only ensure an equitable distribution of federation funds but also vouch for the interests of women during policy decision making. According to a critical mass theory, a strong rather than mere representation of women on boards would bear significant fruit. The theory states that when a size of a group (here, women) reaches a critical mass or certain threshold, that group gains trust and influence (within the larger group, i.e. the whole board). Currently, four out of fifteen members of the IOC (International Olympic Committee) executive board are women (27%) and the percentage of women holding positions in the IOC Commissions are 38%. For the year 2015, the IOC had set a goal of having at least 20% women in all National Olympic Committees (NOC’s) out of which thirty-nine NOC’s had met the mark. Woefully, India’s NOC was in the bottom 10 with a shameful 3.57% of women representation. Research statistics reveal that out of all the National Sports Federations (NSF’s) in India, a staggering eight number of NSF’s {Swimming Federation of India, Volleyball Federation of India, India Rugby Union, etc.} were without any women representation and the remaining NSF’s women constituted 2% to 8% of the governing bodies {Hockey had the highest representation at 34%}. Although India’s National Sports Development Code (2011) supports the protection of gender equality in sports, neither the Code nor any other policy stipulates any minimum percentage for women representation on NSF or NOC boards. Therefore, there should be an onus on Indian Sports Associations to improve the disparity on their governing boards, just like other international countries. India can learn from the United Kingdom’s Code for Sports Governance (2017) wherein Principle 2.1 requires each organization to ensure a minimum of 30% of each gender on its governing board. The intent of this principle is not only to maintain gender parity but also to facilitate open-ended board discussions from both ends of the spectrum.

Also read: India can take a lesson in women’s sport development from Canada

When it comes to other inspiring pro-equality legislation or charters in sports, we may also refer to Title IX, The Brighton Declaration on Woman and Sport, and European Charter of Women’s Rights on Sports. The landmark legislation of 1972 in the United States, Title IX banned sexual discrimination in schools, colleges, and universities by enforcing equal funds for its athletes. Principle 1 of the Brighton Declaration mentions that “Resources, Power and Responsibility” should be allocated fairly and without discrimination by sex, for equality within the sport. Finally, the European Charter of Women’s Rights on Sports mandates sports associations and authorities to adopt regulations that represent men and women equally in decision making positions. But due credit should also be given to the Indian Government for the implementation of sports programmes such as the Panchayat Yuva Krida Aur Khel Abhiyan (PYKKA), now known as Rajiv Gandhi Khel Abhiyan (RGKA), National Playing Fields Association of India, and the Scheme for the creation of urban infrastructure at various levels. All of these have been dedicated to providing both genders access to sports facilities and coaching in urban and rural areas. More significantly, under its empowering initiative of “Khelo India”, section 1.3.9 provides for the funding of sports activities and annual competitions for women especially in sports disciplines where there is lesser participation. And much to our relief, the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports are soon going to release a more comprehensive National Sports Development Code which would also deal with the aspects of sports governance. This Code would have to be strictly complied with by the NOC and the NSF’s. Optimistically, this could compel the percentage of women in sports governance to be improved, say a minimum of 30% of the board. As cliché as it sounds, ‘there is always light at the end of a dark tunnel’. Recently there has been a revolution wherein three football organisations/clubs namely, Lewes FC, Norwegian Football Association, and the New Zealand Football Body have decided to grant equal pay to both its men’s and women’s teams. Even in India, upon Dipika Pallikal’s constant protest for five years, the Senior National Squash Championship had awarded equal prize money to its women. In conclusion, the status of women in sports is bound to improve with time, but there is zilch certainty as to when this discrimination would cease to exist. It is incredibly tough to live the life of a female athlete in this cynical world of ours. Not to leave a sour taste in your mouth, but imagine you are Serena Williams, who has regularly outdone herself and exceeded the potential her body permits and yet gets paid lesser than a tennis male athlete (it is only the grand slams which award equal prize money). Or Place yourself in Sania Mirza’s shoes before the London Olympics when she was put up as ‘bait’ to pacify Leander Paes for the doubles team. Also, sympathise with the anonymous professional boxer from Shillong who shifted to Delhi only to find herself being pinned to the bathroom floor by three men, including her assistant coach, after training. And yet she returned to training within a month. What’s common between these three athletes? They merely wanted to play the sport for their livelihood.

Currently, on an average, a male basketball athlete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) earns the equivalent of ninety-six times the salaries of their female counterparts. This disparity speaks volumes especially when you consider the fact that the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is highest paid women’s league in the World. Another illustration can be seen in the ongoing FIFA Men’s World Cup, wherein the prize money is set at 400 million dollars compared to the 15-million-dollar prize for the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Similarly, the average earners of the English Premier League get paid 100 times more than the women in the equivalent FA Women’s Super League. And finally, to top it all, the Forbes 2018 Highest Paid Athletes does not include a single sportswoman within its top 100.

Currently, on an average, a male basketball athlete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) earns the equivalent of ninety-six times the salaries of their female counterparts. This disparity speaks volumes especially when you consider the fact that the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is highest paid women’s league in the World. Another illustration can be seen in the ongoing FIFA Men’s World Cup, wherein the prize money is set at 400 million dollars compared to the 15-million-dollar prize for the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Similarly, the average earners of the English Premier League get paid 100 times more than the women in the equivalent FA Women’s Super League. And finally, to top it all, the Forbes 2018 Highest Paid Athletes does not include a single sportswoman within its top 100. Also read: The curious case of discrimination in sports earnings

The gender pay gap in the Indian context is pretty much as deplorable, if not exact.

BCCI’s 2018 retainer contracts for its senior men and women players exemplified the same, where the highest earners, i.e. ‘A’ grade women cricketers (Rs.50 L) receive half the pay of the ‘C’ grade lowest earning men cricketers (Rs.1Cr). Also, the men’s team have been offered a salary of 7 crores per annum for cricketers of the ‘A+’ grade or ‘top performers’, leaving behind no such classification for the women’s team. The women of the Indian Football team despite their current World ranking of 59 earn between five to ten lakh rupees, while the men’s team draw around 70 lakhs per year. And yes, the pinnacle sport of India, ‘Hockey’ also has a ten-fold wage gap between both its teams.

BCCI’s 2018 retainer contracts for its senior men and women players exemplified the same, where the highest earners, i.e. ‘A’ grade women cricketers (Rs.50 L) receive half the pay of the ‘C’ grade lowest earning men cricketers (Rs.1Cr). Also, the men’s team have been offered a salary of 7 crores per annum for cricketers of the ‘A+’ grade or ‘top performers’, leaving behind no such classification for the women’s team. The women of the Indian Football team despite their current World ranking of 59 earn between five to ten lakh rupees, while the men’s team draw around 70 lakhs per year. And yes, the pinnacle sport of India, ‘Hockey’ also has a ten-fold wage gap between both its teams. Former FIFA President Sepp Blatter was not only criticised for his sexist comments like “female players could wear tighter shorts” but was also accused of sexually assaulting Hope Solo at a Fifa Ballon d’Or ceremony. Some Indian examples of sexism include that of former Indian cricketer, Snehal Pradhan, and of a female gymnast in the Asian Games of 2014. Snehal Pradhan was a victim of explicit sexism when she was disallowed to participate in several men’s cricket tournaments, primarily due to the lack of regular women setups. And in the latter case of the female gymnast, she was verbally harassed by two coaches (Manoj Rana & Chandan Pathak) through their indecent comments on her clothing. Indian sportswomen have also unsurprisingly been victims of sexual harassment, and one of the most controversial cases was that of the Indian Hockey team. In 2010, thirty-one members of the squad had filed sexual harassment charges against their coach, M.K. Kaushik. In another case, Karnam Malleshwari, Sydney Games bronze winning weightlifter was criticised by P.T. Usha for not bringing up the sexual harassment complaint at an earlier stage, but who could blame her? The list of such unfortunate incidents is endless. This problem is so deep-rooted and rotten within every level of the sports system that many female athletes are reluctant to reach out to competent authorities. Eventually, they end up accepting this ill environment as their fate. Leaving behind the fact that women in this industry are regularly subject to sexist jibes and harassment, they are neither afforded sufficient facilities/opportunities to enhance their sport nor given an incentive to grow into the sport. In the SAF (South Asian Federation) games of 2016, the Indian relay women’s team was put up in a local institute 20 kilometres away from the stadium while the men were accommodated in a close by the four-star hotel, or even when the Sports Authority of India had ignored Dipa Karmakar’s request for her physiotherapist before her vault finals in the Rio Olympics. The fact, that currently the All India Football Federation (AIFF) pursued the participation of the men’s team for the upcoming Asian games in Jakarta-Palembang more than the women’s, manifests the different forms of discrimination faced.‘Sexism in sports is the most common form of discrimination against women’

The Sports Authority of India had ignored Dipa Karmakar’s request for her physiotherapist before her vault finals in the Rio Olympics. Incentive wise, one must look at the prestigious awards dished out by the Government towards its Indian athletes since time immemorial. Because the women sportspersons have been as successful as the male contingent for India, the former only accruing for one-fourth of the overall Arjuna awards reminds us of the gender-biased accolades in India. In toto, gender discrimination is widespread and prevalent in India and multiple other countries. Ranging from sexist posters implemented for cycling races to the FIFA World Cup (Women) being played on artificial turf (compared to the grass field used for the men’s tournament which reduces injury threats), the gender bias situation is nothing short of sad.

The Sports Authority of India had ignored Dipa Karmakar’s request for her physiotherapist before her vault finals in the Rio Olympics. Incentive wise, one must look at the prestigious awards dished out by the Government towards its Indian athletes since time immemorial. Because the women sportspersons have been as successful as the male contingent for India, the former only accruing for one-fourth of the overall Arjuna awards reminds us of the gender-biased accolades in India. In toto, gender discrimination is widespread and prevalent in India and multiple other countries. Ranging from sexist posters implemented for cycling races to the FIFA World Cup (Women) being played on artificial turf (compared to the grass field used for the men’s tournament which reduces injury threats), the gender bias situation is nothing short of sad. So how do we reduce this gender bias or discrimination?

What are those core factors pertinent to such disparity, especially in Indian Sport? Some would say that sexism exists in sport merely because of the patriarchal society and some uneducated elements within it. Others would recommend for a more effective mechanism, in addition to the Internal Complaints Committee, which would deal with sports specific sexual harassment within every level of the system. For example, establishing a central helpline number. This is because hitherto there had been some high profile sexual harassment complaints where either the verdict had been wrongly suppressed or investigation reports had been ignored and unfollowed. Indeed, it is apparent that the ‘Prevention of Sexual Harassment’ annexure in the National Sports Development Code (NSDC), 2011, is not in actual and effective practice. Speaking of which, the Code itself has yet not been amended to completely align with the Sexual Harassment Act of Women at Workplace of 2013. The only proposed document which ensures the compliance of the Sexual Harassment Act by all sports federations in India is the ‘National Sports Ethics Commission Bill 2016 ’ (Clause 16(2)), which is yet under scrutiny. One factor detriment to women in sports is the lack of media coverage on their performances. Currently, in the world, only 4 % of sports media content is dedicated to women’s sport and only 12 % of sports news is presented by women. What’s worse, research has shown us that female athletes were actually covered more in 1989 than recently in 2014. Indian media has also not disappointed us. In its 2002 & 2003 editions, an Indian Sports weekly ‘Sportstar’ had ignored iconic sportswomen like Anju Bobby George (in 2003 she became the first ever Indian athlete to win a medal at the World Athletics Championship with a leap of 6.70 metres), Sania Mirza (first Indian woman to win a Grand Slam tennis title), and the Indian Hockey team (they had won Gold in the 2002 Commonwealth Games and the 2003 Afro-Asian Games). And, a study on Indian media coverage during the 2014 Asian Incheon games revealed that female athletes were treated as second-class citizens compared to the male athletes when it came to publicity in newspapers. “Whenever media tends to cover women’s sports, they do all the fluffy, nice stories, but we want the media to critique performances. Be analytical – something that the media and journalists are with the male side of the game.” – Lisa Sthalekar, a top cricket commentator. Remember, the tennis controversy of equal prize money for Grand Slams? Then Indian Wells Champion, Novak Djokovic, had commented that men deserved better pay because the public was more interested in their games over the women’s; hence a more significant viewership revenue. This was said in the context of Raymond Moore’s (Director of Indian Wells) opinion that tennis women stars should be thankful to people like Roger Federer and Raphael Nadal. Only after severe criticism did they apologise for their comments, but coming back to Djokovic’s argument, would it stand? This stance originates from the idea that since the men’s tournament brings in more money to the association or federation concerned than the women’s, it would only be fair to give the men their deserved share. In its 2002 & 2003 editions, an Indian Sports weekly ‘Sportstar’ had ignored iconic sportswomen like Anju Bobby George (in 2003 she became the first ever Indian athlete to win a medal at the World Athletics Championship with a leap of 6.70 metres), Sania Mirza (first Indian woman to win a Grand Slam tennis title), and the Indian Hockey team (they had won Gold in the 2002 Commonwealth Games and the 2003 Afro-Asian Games) Not only is this argument rudimentary but also baseless. Just because of two reasons: One, comparing men’s sports and their abilities to women is like comparing apples with oranges. Two, men and women in games have not yet been placed on the same levelling ground for any sort of comparison, in the sense that women do not receive a similar kind of media coverage. Let me explain this vicious cycle. If female athletes do not receive sufficient media publicity, how can you expect a person to be inspired or interested in women’s sports especially when he or she has not witnessed the same on television or the news? Previously mentioned numbers endorse such a counter-argument. Further, if you integrate it with the remaining discriminatory elements which are likely to discourage the young girls, the sport would end up with fewer women. Less female sportspersons mean lesser publicity, i.e. smaller viewership revenue. Therefore, the cycle is never-ending because from every angle it can be seen that men and women have never been placed on an equal footing in the sports industry. Nonetheless, it is firmly believed that a more significant reason for the inequality is the lack of representation of women on boards of National Federations or Olympic Committees. A substantial majority of women on decision-making boards of such organisations can not only ensure an equitable distribution of federation funds but also vouch for the interests of women during policy decision making. According to a critical mass theory, a strong rather than mere representation of women on boards would bear significant fruit. The theory states that when a size of a group (here, women) reaches a critical mass or certain threshold, that group gains trust and influence (within the larger group, i.e. the whole board). Currently, four out of fifteen members of the IOC (International Olympic Committee) executive board are women (27%) and the percentage of women holding positions in the IOC Commissions are 38%. For the year 2015, the IOC had set a goal of having at least 20% women in all National Olympic Committees (NOC’s) out of which thirty-nine NOC’s had met the mark. Woefully, India’s NOC was in the bottom 10 with a shameful 3.57% of women representation. Research statistics reveal that out of all the National Sports Federations (NSF’s) in India, a staggering eight number of NSF’s {Swimming Federation of India, Volleyball Federation of India, India Rugby Union, etc.} were without any women representation and the remaining NSF’s women constituted 2% to 8% of the governing bodies {Hockey had the highest representation at 34%}. Although India’s National Sports Development Code (2011) supports the protection of gender equality in sports, neither the Code nor any other policy stipulates any minimum percentage for women representation on NSF or NOC boards. Therefore, there should be an onus on Indian Sports Associations to improve the disparity on their governing boards, just like other international countries. India can learn from the United Kingdom’s Code for Sports Governance (2017) wherein Principle 2.1 requires each organization to ensure a minimum of 30% of each gender on its governing board. The intent of this principle is not only to maintain gender parity but also to facilitate open-ended board discussions from both ends of the spectrum.

In its 2002 & 2003 editions, an Indian Sports weekly ‘Sportstar’ had ignored iconic sportswomen like Anju Bobby George (in 2003 she became the first ever Indian athlete to win a medal at the World Athletics Championship with a leap of 6.70 metres), Sania Mirza (first Indian woman to win a Grand Slam tennis title), and the Indian Hockey team (they had won Gold in the 2002 Commonwealth Games and the 2003 Afro-Asian Games) Not only is this argument rudimentary but also baseless. Just because of two reasons: One, comparing men’s sports and their abilities to women is like comparing apples with oranges. Two, men and women in games have not yet been placed on the same levelling ground for any sort of comparison, in the sense that women do not receive a similar kind of media coverage. Let me explain this vicious cycle. If female athletes do not receive sufficient media publicity, how can you expect a person to be inspired or interested in women’s sports especially when he or she has not witnessed the same on television or the news? Previously mentioned numbers endorse such a counter-argument. Further, if you integrate it with the remaining discriminatory elements which are likely to discourage the young girls, the sport would end up with fewer women. Less female sportspersons mean lesser publicity, i.e. smaller viewership revenue. Therefore, the cycle is never-ending because from every angle it can be seen that men and women have never been placed on an equal footing in the sports industry. Nonetheless, it is firmly believed that a more significant reason for the inequality is the lack of representation of women on boards of National Federations or Olympic Committees. A substantial majority of women on decision-making boards of such organisations can not only ensure an equitable distribution of federation funds but also vouch for the interests of women during policy decision making. According to a critical mass theory, a strong rather than mere representation of women on boards would bear significant fruit. The theory states that when a size of a group (here, women) reaches a critical mass or certain threshold, that group gains trust and influence (within the larger group, i.e. the whole board). Currently, four out of fifteen members of the IOC (International Olympic Committee) executive board are women (27%) and the percentage of women holding positions in the IOC Commissions are 38%. For the year 2015, the IOC had set a goal of having at least 20% women in all National Olympic Committees (NOC’s) out of which thirty-nine NOC’s had met the mark. Woefully, India’s NOC was in the bottom 10 with a shameful 3.57% of women representation. Research statistics reveal that out of all the National Sports Federations (NSF’s) in India, a staggering eight number of NSF’s {Swimming Federation of India, Volleyball Federation of India, India Rugby Union, etc.} were without any women representation and the remaining NSF’s women constituted 2% to 8% of the governing bodies {Hockey had the highest representation at 34%}. Although India’s National Sports Development Code (2011) supports the protection of gender equality in sports, neither the Code nor any other policy stipulates any minimum percentage for women representation on NSF or NOC boards. Therefore, there should be an onus on Indian Sports Associations to improve the disparity on their governing boards, just like other international countries. India can learn from the United Kingdom’s Code for Sports Governance (2017) wherein Principle 2.1 requires each organization to ensure a minimum of 30% of each gender on its governing board. The intent of this principle is not only to maintain gender parity but also to facilitate open-ended board discussions from both ends of the spectrum. Also read: India can take a lesson in women’s sport development from Canada

When it comes to other inspiring pro-equality legislation or charters in sports, we may also refer to Title IX, The Brighton Declaration on Woman and Sport, and European Charter of Women’s Rights on Sports. The landmark legislation of 1972 in the United States, Title IX banned sexual discrimination in schools, colleges, and universities by enforcing equal funds for its athletes. Principle 1 of the Brighton Declaration mentions that “Resources, Power and Responsibility” should be allocated fairly and without discrimination by sex, for equality within the sport. Finally, the European Charter of Women’s Rights on Sports mandates sports associations and authorities to adopt regulations that represent men and women equally in decision making positions. But due credit should also be given to the Indian Government for the implementation of sports programmes such as the Panchayat Yuva Krida Aur Khel Abhiyan (PYKKA), now known as Rajiv Gandhi Khel Abhiyan (RGKA), National Playing Fields Association of India, and the Scheme for the creation of urban infrastructure at various levels. All of these have been dedicated to providing both genders access to sports facilities and coaching in urban and rural areas. More significantly, under its empowering initiative of “Khelo India”, section 1.3.9 provides for the funding of sports activities and annual competitions for women especially in sports disciplines where there is lesser participation. And much to our relief, the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports are soon going to release a more comprehensive National Sports Development Code which would also deal with the aspects of sports governance. This Code would have to be strictly complied with by the NOC and the NSF’s. Optimistically, this could compel the percentage of women in sports governance to be improved, say a minimum of 30% of the board. As cliché as it sounds, ‘there is always light at the end of a dark tunnel’. Recently there has been a revolution wherein three football organisations/clubs namely, Lewes FC, Norwegian Football Association, and the New Zealand Football Body have decided to grant equal pay to both its men’s and women’s teams. Even in India, upon Dipika Pallikal’s constant protest for five years, the Senior National Squash Championship had awarded equal prize money to its women. In conclusion, the status of women in sports is bound to improve with time, but there is zilch certainty as to when this discrimination would cease to exist. It is incredibly tough to live the life of a female athlete in this cynical world of ours. Not to leave a sour taste in your mouth, but imagine you are Serena Williams, who has regularly outdone herself and exceeded the potential her body permits and yet gets paid lesser than a tennis male athlete (it is only the grand slams which award equal prize money). Or Place yourself in Sania Mirza’s shoes before the London Olympics when she was put up as ‘bait’ to pacify Leander Paes for the doubles team. Also, sympathise with the anonymous professional boxer from Shillong who shifted to Delhi only to find herself being pinned to the bathroom floor by three men, including her assistant coach, after training. And yet she returned to training within a month. What’s common between these three athletes? They merely wanted to play the sport for their livelihood.

Next Story