Football

Eclipsed brilliance, fabricated football: Prasanta Sinha, a mindless Maidaan miss

Reacting to Maidaan, Sinha's daughter Sonali told The Bridge it is 'painful to watch the movie and see my father on the reserve bench during the semifinal and final'.

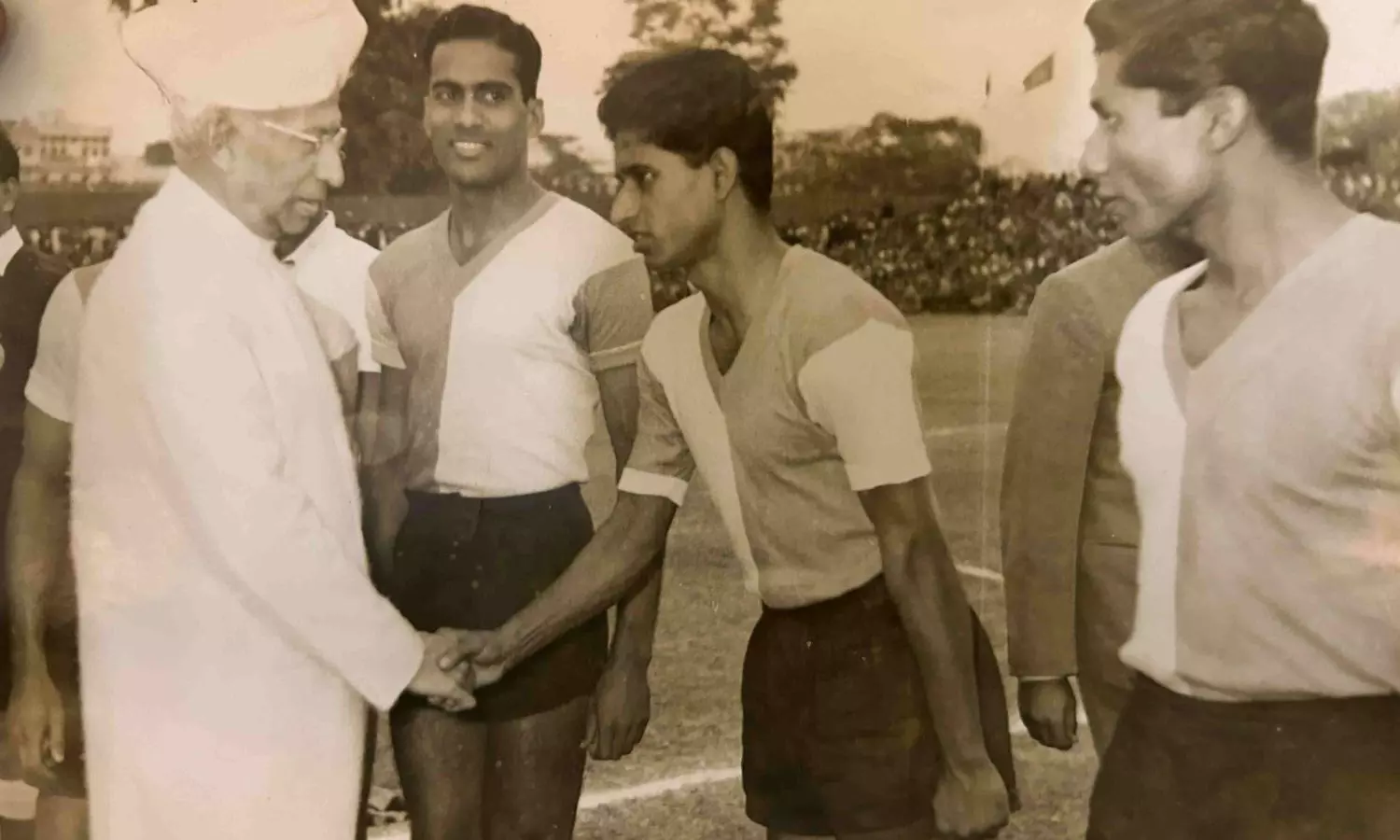

Prasanta Sinha with President of India Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan in East Bengal colours. (Photo credit: Special Arrangement)

Maidaan, starring Ajay Devgn as Syed Abdul Rahim, is a story about the golden era (1951-1962) of Indian football and how coach Rahim sparked a revolution through his tactical brilliance, guiding India to victory at the 1962 Asian Games.

Directed by Amit Ravindernath Sharma, Maidaan is “supposed” to be a biographical drama of Rahim and the Indian football team attaining the gold medal in the Jakarta Asiad in 1962.

While the film has captivated audiences with its storytelling and made them aware of Rahim’s contribution to Indian football, it has also been in the spotlight for some of its factual inaccuracies.

Imagine standing before a “masterpiece’- a slice of history, carefully curated from the archives, promising to tell a tale of inspiration through sports- only to realise, or worse, not realise; how facts have been distorted to do the same.

In an exclusive conversation with The Bridge, Sonali Sarkar, daughter of the late Prasanta Sinha, brought forth the discrepancies regarding the portrayal of events in the film.

Prasanta Sinha, a stalwart for Indian football, who was an integral part of the “Class of 62”, was inaccurately depicted in the film.

After a remarkable comeback following a defeat to South Korea in the first match, Rahim had made a big tactical decision when he opted to play Sinha ahead of Ram Bahadur in the semifinal, and following that in the final.

Despite Ram Bahadur’s recovery before the final, coach Rahim insisted on sticking with Prasanta Sinha, firmly believing in his abilities.

But Sinha’s inclusion in the squad ahead of experienced Mariappa Kempaiah was a surprise in itself.

Rahim had believed an ageing Kempiah had slowed down and instead preferred Sinha’s positional play. Sinha had also confided to his roommates, Arun Ghosh and P. Burman, that he would not get a chance ahead of the experienced Franco and Bahadur.

According to many reports, Rahim, being a strict disciplinarian, had started doubting Ram Bahadur’s commitment after an incident at the Asian Games Village. Many reports also state that Ram Bahadur was injured before the semifinal which led to the inclusion of Prasanta Sinha in the playing eleven.

Prasanta was asked to play as a left midfielder with Franco and Yusuf Khan in support. He played with such bold gusto in the semifinal that he was included in the final against South Korea. It is worth noting that Ram Bahadur did not play a lot for India after the 1962 Asiad. And just like always, Rahim was spot on with his instinctive judgement.

“In our childhood, whenever PK uncle (PK Banerjee) or Arun (Ghosh) uncle visited our house, they used to tell these stories. Ram Bahadur and my father were great friends, it was just a tactical decision of Rahim Saab. They remained good friends even after that,” said Sonali.

However, there was no mention of Prasanta Sinha in the movie. As per the film, Ram Bahadur continued to play both in the semifinal and final. The film even went on to depict Bahadur advancing with the ball, creating passes.

To add to the diegetic world of the movie, there is a scene where Peter Thangaraj calls out “Ram” instead of “Sinha”, to pass the ball which led to the winning goal scored by Jarnail Singh. Does this qualify as a distortion of facts? Certainly, yes. Does this qualify as conscious bias? That is for the filmmakers to answer.

“It was incredibly painful to watch the movie and see my father on the reserve bench during the semifinal and final, which is absolutely false. We have grown up listening to these stories not just from my father but from everyone who knew and adored him. These are cherished memories that have been unfairly altered,” Sonali added.

The omission of Sinha's character from the lineup is not merely a cinematic oversight; it is a disservice to his legacy and a missed opportunity to celebrate a true sporting hero. By neglecting to acknowledge his pivotal role in shaping Indian football history, the film has inadvertently perpetuated a narrative that diminishes and misremembers the contributions of heroes like Sinha.

“It was not about my grandfather’s omission from the movie that hurt us. Replacing his story with someone else, who also deserves to tell his own story, is really disheartening. We went to watch the movie with less expectations since the filmmakers hadn’t reached out to us before, but we didn’t expect this- my grandfather being sidelined on the bench, when in reality he provided the assist for the winning goal to Jarnail Singh,” stated Pallavi Sarkar, granddaughter of Sinha.

How can one make a film about the legacy of one great by undermining the legacy of another? Prasanta Sinha was not just a one-tournament wonder. He made his debut for India in that semifinal, then went on to represent East Bengal from 1964-1971, also captaining the club in 1967.

During his tenure at the club, East Bengal won the CFA and the IFA Shield thrice, the Durand Cup and Rovers Cup twice, and the Bordoloi trophy once. It is of utmost shame that legacies like his are forgotten.

It is a delicate balance to make a movie about sports and make a historical biography about a sportsperson - the latter has to be backed by evidence for there are people who are not just connected to these stories but have lived them. Can we then trust the film industry to make stories like these? Do we blame them for overlooking facts like these? The answer lies in criticism, conversation and acknowledgement.

In a sporting landscape dominated by larger-than-life narratives and superstar personas, it is all too easy for the stories of individuals like Prasanta Sinha to be overlooked and forgotten. However, it is imperative that we strive to rectify this oversight and ensure that his legacy is rightfully recognized and celebrated.

As we continue to tell more stories about Indian sports through films, let us not allow legends to be relegated to obscurity. Instead, let us honour their memory, preserve their legacy, and inspire future generations to emulate their passion. There is no medium more powerful than cinema to tell stories like these. There is no excuse for overlooking contributions like these. We cannot let these stories go into oblivion.