Football

Football in India, and how the sport helped India seek a viable identity

In the late 1890s, the Bengali community viewed football as a means of expressing their masculinity and potential superiority. Soon, the football pitch became an arena for cultural conflict which was fought out through the game, instead of being a means through which the British could signify their segregation from the colonised.

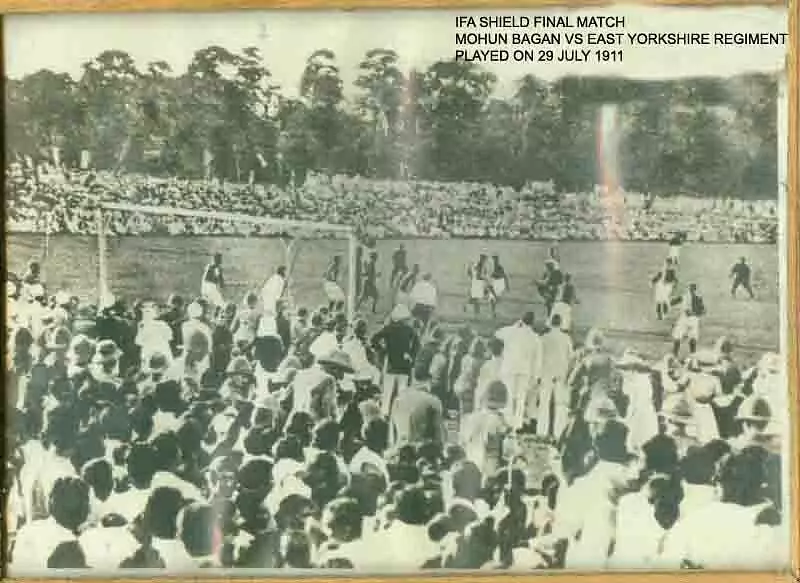

Image Source : Mohun Bagan

India is a complicated country. It's fraught with beauty, hypocrisies, ironies and conundrums. That might pertain to innumerable things that create divisions amongst the masses, seek to create factions and barely bring about any bit of unity in this country which is unique in it's own way. As tough as it might be to decipher, we recently witnessed something which united the country as a whole. Neeraj Chopra winning Gold at the Olympics brought people of India close in a manner in which no other power could.

Bar the flow of charade that followed which had people clamoring for a piece of the Olympian Neeraj, a lot of the celebrations were pure. It gave a real community feeling which has become rare in a country that has had a raft of ideological disputes. People, for some days, seemed on the same page and no divisions on the basis of economics, politics, religion existed. Probably the same happened when India beat England at Lords in rather dramatic circumstances.

It was elation - almost like nothing else mattered. It makes you wonder about the power that sport possesses but it escapes the attention of many that sport was a key reason for the very birth of the feeling of nationalism in India. It might escape our attention because sport is still low down in the pecking order in our society but the roots of it lie in West Bengal, where football helped in challenging the imperial powers in India.

Back in the late 1890s and early 1900s, football had become a key part of the Indian social framework. It was brought to the shores by the East India Company and it initially took hold in the ports, largely because it was played for the sailors and soldiers of those areas. Kolkata was the centre of imperialism in the country and became the hotbed of the colonialists, who were keen on using sport and football in the same way as they had back in England in the 1800s.

When the Empire was flailing, there was a need for the British to use football as a means of preaching 'manliness', teamwork and strength. It was inculcated into schools to bring about those values amongst boys from a very young age. It was a stark contrast to how football was perceived back in the 1200s, when the kings would look down upon the game for being uncivilised and unruly. In the mid-1800s, it was being seen as a source of reform in England and in Bengal, it was incorporated into the curriculums of schools to teach children about obedience and masculinity.

In other parts of the country, football was used as a means of making masses more 'Christian' or supposedly more 'civilised'. But it was in Bengal that the game quickly became a part of a cultural battle against imperialists. As the soldier regiments across the major cities formed clubs of their own, the game was serving the purpose of keeping Indians and the imperialists apart. The British had used a similar strategy in South America as well, as they saw football as an instrument to separate themselves from the inhabitants. And as it was the case in South America, politics in India made a complete separation through football impossible.

A prime reason for the inculcation of football was rooted in the fact that the Bengali community wasn't viewed as a 'military community'. To prove the opposite, the communities initially tried to ignore western sports like football. But over time, their attempts to prove the imperialists wrong proved futile and they took up football as a cultural tool to unite themselves against the negative perception that the British carried for them.

In the late 1890s, the Bengali community viewed football as a means of expressing their masculinity and potential superiority. Soon, the football pitch became an arena for cultural conflict which was fought out through the game, instead of being a means through which the British could signify their segregation from the colonised.

Football historian David Goldblatt has stated that while rebels for the Revolt of 1857 came from different communities and areas, rebels from Bengal were key and towards the end of the 1890s, Bengalis were often excluded from the security apparatus of British India. It just ties into how the British viewed Bengalis to be 'weak' and unreliable for tasks that pertained to physical activity.

Many Bengali graduates of the new elite schools created sports clubs and gradually, this created a sports culture in the community - as they aimed to prove the British wrong by uniting for a motion.

Playing barefoot against the booted British became a sign of the cultural battle and the unity of the Bengali community and it was the encapsulation of nationalism against the colonisers in a true form. The maidan became the arena for this cultural warfare and any win against a British team was seen as nationalism's win over the evil of colonialism.

The Trades Cup final of 1892 saw Sovabazar oust British team East Surrey Regiment to claim the title, but it was Mohun Bagan's success and their very identity that played a key role in the accentuation of this cultural war.

The club was founded by the Bengali aristocrats and intelligentia and carried a nationalistic aim. They wanted to create a name for Bengali masculinity and activities that stuck as a stereotype to the community were banned in the clubhouse. This included drinking and smoking and the club made sure that income was always available for the players who didn't have employment. In some ways, it was a community club in the most perfect sense.

It had an identity, a culture, a notion and a certain set of rules which members had to follow. And this proved key in what was to come. The partition of Bengal in 1905 only accentuated the feeling of animosity in Bengal towards the British and while their reasons for the action were portrayed to be simply administrative, that wasn't really the case. Football was now increasingly seen as one important way to sometimes prove their might.

Mohun Bagan won three Trades Cups in a row in the early 1900s, also winning the Cooch Behar Cup twice and winning the Gladstone Trophy once. In the process, they also kept picking up important wins against English sides, constantly giving Bengalis something to not just look forward to but also something to cheer for when the imperialists were trying to divide the country.

People all across Bengal celebrated their wins over European sides and it was clear that Indian football was acquiring an image, a culture and something which had an aim. This surge of nationalism through football came at the right time, as Mohun Bagan defeated East Yorkshire regiment in the IFA Shield Final of 1911.

About 60,000 people were present at the Maidan to witness the game and arrangements were made for people to commute from the maidan to the places around Bengal. An article from the Manchester Guardian has stated that people from all religions and classes chanted 'Vande Mataram' as they headed to the maidan, as the bare-footed Indian team came back from a goal down to win 2-1.

This was seen as a massive win not just for the club, but for the country. Mohun Bagan were fulfilling their nationalistic identity and the wave of nationalism was enhanced. Kausik Bandopadhyay has stated in his works that this became a time when the term 'Indians' was being used synonymously for 'Indians'. It was a clear indicator of how it wasn't a win for a community, the joy was all-encompassing.

When the club had to defend the IFA Shield in 1912, two of their legal goals were disallowed for offside in a move that was seen as 'revenge' by the British. Despite the increasing influence of Indian football, no Indians were allowed on the Indian Football Association and this led to Indian clubs boycotting the Calcutta League in the 1930s. After a point, the British had no choice but to capitulate and hand Indians and Indian clubs enough representation in all footballing boards and competitions.

The shift of the Indian capital to Delhi in 1911 is now seen as a rather uninteresting event in Indian history now, Ramchandra Guha has pointed out in his works that the impact and momentum which football gave to the movement has often gone 'unnoticed'. He believes that the connection between sporting success of India's football clubs and anti-colonialism is often undermined.

It was seen as the recovery of self-respect and dignity for the country, more than the region of Bengal. Bandopadhyay argues that football became the home for pent-up nationalism. The affluent class was reluctant in taking direct part in the nationalist movement and the youth were not willing to get involved in direct confrontation either. The working class couldn't show their resentment openly because they worked under the colonialists themselves. So football allowed them to express themselves in different ways and it was a place where nothing could really stop them.

In more ways than one, football was the source of coalescence for Indians across castes, religion and class. While it did become the hotbed of division along the same lines when political involvements around 1947 stepped in, but the game did a rather undervalued job in uniting the nation in a rather subtle manner. It may not get credit, but when thousands of Indians were in the same voice when Neeraj Chopra won Gold in the Olympics, nothing else really mattered.

And when the British thought they could rule India and our countrymen had nothing to lose, football helped them seek a viable identity.