Featured

What drives gymnasts to perform under the most challenging conditions?

The darling of Indian gymnastics, Dipa Karmakar missed out on a medal at the Olympic Games in 2016, finishing fourth in a packed field of competitors. Very quickly, she became the star of Indian gymnastics and the people were keen to see what would come next. But Dipa and her coach had bigger problems to deal with. One that would seal the fate on whether she could continue her journey in gymnastics. Following the Games, Dipa tore a ligament in her knee that required surgery. No one would have blamed her for retiring and taking a break from the sport. But Dipa was relentless. She worked in the shadows made a surprise comeback for the Asian Games the very next year, following which she also competed at the Turkey World Cup, winning the gold medal on vault!

At a young age, Dipa was able to withstand immense pressure, carrying the dreams of a country on her shoulders. What is it about us human beings that allows us to display such extraordinary courage and performance under the most challenging conditions?

This is often referred to as psychological resilience. Simply, it is defined as an individual’s ability to exercise personal qualities to withstand pressure. (2) As coaches, we are often looking for athletes with such innate talent. We readily welcome athletes who are tough, mentally and physically and do not crumble in the face of adversity. What if there was a way, we could nurture such qualities? What if as a coach, you could build an environment that fosters such resilience? If you are looking to develop this valued quality, then this blog is for you!

The Mental Fortitude Training (MFT) Program

The MFT program is an evidence-based approach to building resilience and sustaining success for athletes. Using research conducted on British athletes, during their preparation for the London 2012 Olympics, researchers have collected information about resilience in high-performance environments and developed a mental fortitude training program.

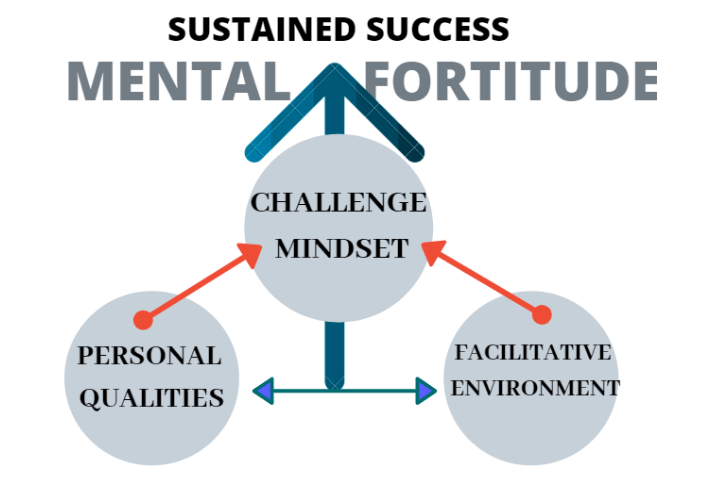

Using the framework of the mental fortitude training (2), this blog lays down key features of building resilience in gymnasts through three aspects. Nurturing psychological qualities, creating a facilitative environment and developing a challenge mindset.

Understanding psychological resilience

Psychological resilience is referred to as the positive response and adaptation to an adverse event. (3) or “defined as the role of mental processes and behaviour in promoting personal assets and protecting an individual from the potential negative effect of stressors.” (4)

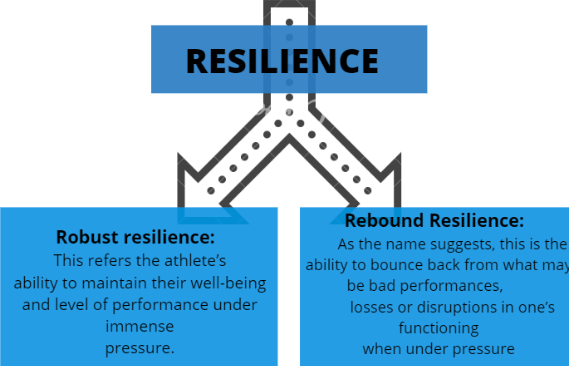

Within MFT two types of resilience are described:

The Kerri Strug story beautifully demonstrates the two types of resilience, through her ability to maintain her mental wellbeing in a high-pressure situation and bounce back from an error to deliver a top-class performance, a quality we aim to foster in our athletes.

The MFT program explains the three areas that facilitate the process of building resilience:

- Personal Qualities

- Facilitative Environment

- Challenge mindset

Personal qualities

When discussing this element of the training program, the discussion about the gymnast’s personal characteristics becomes crucial. Personal qualities are the athlete’s psychological factors that shield them from stressors or negative events.(2) These personal qualities can be divided into an individual’s inherent personality and psychological skills.

While an individual’s personality is usually more enduring and difficult to change since it is developed over a long time, the psychological skills are. These are cognitive techniques used by people that help enhance their performance in any domain. For gymnasts, developing these psychological skills can help in increasing tolerance to withstand pressure and stress.

Here are some examples of processes through which personality characteristics such as optimism, confidence and self-esteem can be instilled:

Goal setting

You can include the gymnast’s opinion in determining goals and devise a plan to attain them in a certain time frame. Including the gymnast in this decision making process and taking their opinion will increase their desire to reach the goal while also building self-esteem and confidence in themselves.

Imagery

Starting off and ending training sessions with short visualisation sessions, where gymnasts can visualise the ideal routine they would wish to compete and accordingly set goals and create mental images for themselves.

Belief in one’s ability

Introducing a system where gymnasts end training sessions with a debrief wherein each gymnast can reveal their highlight of the day, whether they performed new skills, overcame fears or something they believe they could improve on. Through this, we push gymnasts to acknowledge the small victories and continue to have high self-efficacy.

“I think that everything is possible as long as you put your mind to it and you put the work and time into it. I think your mind really controls everything," said Micheal Phelps, most decorated Olympian of all time.

Facilitative environment

As human beings, we are constantly influenced by our environment and the presence of others in it. Therefore, it is evident that as coaches, we consider the broader environment we are creating for our athletes. The most ideal environment for fostering resilience and high-quality performance has been proved to be one that offers high challenge and high support to its athletes.

Challenge

In a sporting context, coaches often set high standards for their athletes, introducing challenging situations to avoid stagnating environments. This helps athletes become accountable and assume responsibility for their actions and goals. When they are challenged and are striving to achieve targets, it creates a motivated environment. (5)

Support

This includes providing the opportunity to your athletes to develop their personal qualities, and promote a learning environment.

This could include the people in the environment who are in contact with the athletes. Research on elite gymnasts found coaches, teammates and sports psychologists to be major influences. (5)

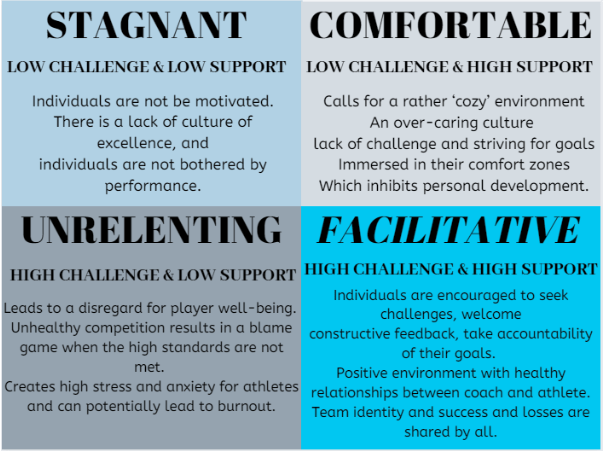

Types of environments (2)

Based on the availability of challenge and support to the athlete, four types of environments can emerge:

The aim for any coach must be to promote a facilitative environment not just for sustained success but more importantly, to ensure the wellbeing and positive attitudes of its individuals.

In sports like gymnastics, that are characterised by high-pressure situations and require countless hours of training, a proven effective method of producing such an environment is through Pressure Inurement Training. (2)

Pressure Inurement Training (PIT)

In competition, gymnasts are expected to deliver top-class routines with perfection in extreme pressure situations. Creating an environment that gradually immunises the gymnast to handling pressures in such situations, could greatly improve performance and develop resilience. (6) Manipulating the environment and slowly increasing the challenge and pressure on an individual through Pressure Inurement Training is one method. (2)

For instance, your gymnast has a problem performing a beam routine without falling. She may be good at this event but tends to second guess herself and get nervous in challenging situations. The ability to maintain her composure and fight such feelings is crucial to her gymnastics success. Using the stepwise approach to PIT will be beneficial:

- Once she has mastered the technicality of the skills and is able to perform it in training, the aim is to gradually immunise her to a competitive setting.

- Gradually, pressure on the individual can be increased via challenge. This can be done in the form of gathering gymnasts in the club and making the gymnast perform a routine while there is music playing in the background, which mimics competition settings.

- This is categorised as increasing the demand of competitive stressors.

- Introducing novelty in the training, through changing the location of certain equipment, or scheduling a surprise mock competition could create situations that bring gymnasts outside their comfort zones and encourage adaptability.

- Another way to introduce PIT is through the increasing significance of appraisals or goals. Here, gymnasts can be given a certain time frame, in which time they must show skills they wish to compete successfully in training (7) based on which they will be added into their competitive routines. Coaches often use this by giving gymnasts tasks, where they must complete five out of seven routines without any significant errors, for routines to be competition ready.

While the increasing challenge is a great way to foster resilience, an environment that doesn’t equate it with the necessary support, will most likely not succeed in their PIT.

Coaches and psychologists must carefully track the gymnast’s reaction to different manipulations. This includes a psychological response, effect on performance and their well-being. Therefore when:

- The demand or pressure placed on the gymnast exceed the available resources, it results in negative outcomes and hindered performance. This scenario is an indication that an increase in support and motivational feedback is required. Therefore, the challenge can be reduced to first ensure the well-being and coping ability.

- However, if gymnasts have displayed positive responses to pressure, they are ready for the further challenge with increased developmental feedback as well.

Challenge Mindset

The program aims to aid gymnasts in being able to understand and evaluate the pressures they face in a positive manner aptly utilizing their resources and thoughts to make decisions. (2) This will inevitably be guided by the personal qualities they possess and the presence of a facilitative environment helping them develop and endure a challenge mindset that fosters resilience.

Research suggests, during stressful situations, individuals use a process of primary and secondary appraisal, whereby they first prioritise the significance of an event and then judge the situation, either positively or negatively. (2)

Let’s look at this using the example of popular American gymnast, Vanessa Atler. Powerful and naturally built for floor and vault events, many thought she was a lock for the 2000 Olympics team. However, uneven bars never came naturally to her and she started developing a block on some of the skills. Falling on the event at multiple competitions, it became her worst nightmare. She began engaging in negative thinking patterns (2) such as:

End of the world thinking

She started believing that she would never be able to successfully perform a bars routine, presuming the worst of her performances.

It can’t be done thinking.

Similarly, she would believe that she would never be able to catch her releases on bars and continuously fail before the event had occurred.

Second-guessing

She had mentioned how she would tell the media that her training went well, and she was embarrassed by what they would think if she fell. This is typical of second-guessing and creating negative thought processes for oneself.

For gymnasts with such personalities, it is a challenge to keep them positively engaged in their performance and self-belief. In conjunction with continuously developing psychological skills and maintaining the facilitative environment, thought regulation strategies are one way to help the gymnast refrain from such thinking patterns.

It is not surprising to find gymnasts often get demotivated and begin catastrophizing situations where performances don’t go to plan. Training gymnasts from refraining to engage in such thinking before it occurs is proven to be useful for developing a resilient athlete. (5)

Psychologists suggest using thought regulation strategies that could be cued to gymnasts that they are engaging in a vicious cycle of negative thought. Some examples are:

Stop

Teaching your gymnasts to use cue words or phrases like “breathe!” or “stop!”, when they begin doubting themselves. For instance, it is common for gymnasts to feel nervous before a beam routine, incorporating a dance step into the routine that works as a cue to remind them to breathe and recompose in case of any errors to aid this strategy.

Verbalise

Talking to coaches, senior gymnasts or teammates about negative thoughts or feelings could teach gymnasts to verbalise their difficulties and help replace it with positive thoughts. Gymnasts can help each other and build a stronger team environment concurrently.

Confront

When confronted with difficulty or negativity, encourage gymnasts to confront their thoughts. Push them to ask themselves to rationalize the situation, for eg: if you fell on your vault, was that the worst thing that could happen? Was that your last competition? What did you learn from it that help you better it in the future? If it was your teammate who fell, how would you consider helping her see the brighter side?

Another important quality to instil in gymnasts is the presence of mind. In competition, small errors may occur in routines and require gymnasts to quickly alter sections of the exercise. As a coach, you want your gymnast to be able to make a wise decision within seconds to save major mistakes from occurring in competition. Addressing such situations in training and pushing gymnasts to look for solutions by creating such scenarios can reduce stress and anxiety in the competition (8) and promote confidence, a quality deemed vital to success in the stress-resilience performance relationship. (4)

The ability to perceive any situation as a learning experience, be open to criticism and take positives from it (9) takes immense understanding on the part of the athlete and usually a ‘work in progress’. As athletes mature and gain experiences together with their immersion in a facilitative environment and practising their psychological skill, it facilitates this challenge appraisal and a positive personality (4) to flourish, creating a gateway for success and truly believe in what John Maxwell (10) calls the ‘ you either win or you learn’ mentality.

“Notice what comes first? Attitude. You cannot achieve anything, I believe, unless you bring the right attitude to the pool, to the classroom, to the office—even to the family room,” said Bob Bowman, coach of Micheal Phelps.

The coach equation: Where do you fit in?

The coach-athlete relationship is crucial in a sports context. The proximity of coach and athlete reveal the critical role coaches play in athlete development (11) and motivation. (12) The complex interactions between coaches and athletes bring about successful performance accomplishments. (13) As coaches, there is often great pressure to deliver successful performances. In gymnastics, one coach usually has a number of gymnasts they are responsible for, which makes it increasingly difficult to personally attend and create an MFT program for every athlete. We understand this difficult position that you come from. Therefore, we believe as a coach, if you succeed in building an environment that fosters resilience and promotes a healthy culture of excellence, half your battle is won. Working together with the psychologist, emphasis on building personal qualities of gymnasts can be laid which will shape a challenge mindset for your gymnasts.

Breaking down the elements of the MFT program and using resources wisely will reduce stress on you as the coach, and help promote a culture of resilience and excellence.

Some tips for implementation

Effective goal setting (2,8): Encouraging gymnasts to acknowledge their strengths and weaknesses on events and providing autonomy (14) in determining short and long-term achievable goals will help them assume responsibility for them and ignite their inner desire to achieve them.

Supportive communication: In our sport, coaches and gymnasts often spend a great deal of time together ever since the gymnasts are very young. Creating a gateway honest interactions and building a relationship of trust, where gymnasts can freely share thoughts with the coach will maintain a healthy environment in the gym and gymnasts will feel cared for. (5) A strong coach-athlete relationship is a marker of athletic success. (15)

Using pressure as a positive (16): As an influential role model for your gymnasts, if you endorse a culture where pressure is viewed as a situation or opportunity for thriving, it can percolate to your gymnasts. Using the pressure of an upcoming competition as fuel to motivate your gymnasts to strive farther, can be one method.

Mistakes are not a bad thing: In a sport defined by its aim for perfection, it is easy for coaches and gymnasts alike to get blinded by this aim. It is important to remind your athletes that is okay to make mistakes. The learning process involves making mistakes and learning how we can become better. Every human being has a breaking point, there’s only that much we can push, and get pushed! Our job as coaches is to help the gymnast be the best version of themselves and mistakes and learning is an essential part of that journey.

The MFT program presents an understanding and precise method to foster resilience. it can be readily applied to gymnastics contexts and I hope it has added value to your philosophy on coaching and will aid you in your coaching endeavours.

“In the end, it’s about the teaching, and what I always loved about coaching was the practices. Not the games, not the tournaments, not the alumni stuff. But teaching the players during practice was what coaching was all about to me. “

John Wooden, American Basketball Coach

Thank you for taking the time to read my blog. Please feel free to share it and if you have any questions or feedback, leave a comment in the section below!

REFERENCES

1. Gymnast Strug motivates others with story of gold [Internet]. U.S. 2019 [cited 18 December 2019]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-oly-gymn-wstrug/gymnast-strug-motivates-others-with-story-of-gold-idUSBRE85R0AQ20120628

2. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action. 2016;7(3):135-157.

3. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological Resilience. European Psychologist. 2013;18(1):12-23.

4. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2012;13(5):669-678.

5. Thelwell R, Such B, Weston N, Such J, Greenlees I. Developing mental toughness: Perceptions of elite female gymnasts. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2010;8(2):170-188.

6. Sarkar M. Developing resilience in elite sport: the role of the environment. The Sport and Exercise Scientist. 2018;(55):1.

7. White R, Bennie A. Resilience in Youth Sport: A Qualitative Investigation of Gymnastics Coach and Athlete Perceptions. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. 2015;10(2-3):379-393.

8. Kegelaers J, Wylleman P. Exploring the Coach’s Role in Fostering Resilience in Elite Athletes. American Psychological Association. 2018;8(3):239-254.

9. Crust L, Clough P. Developing Mental Toughness: From Research to Practice. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action. 2011;2(1):21-32.

10. Maxwell J. Sometimes you win, sometimes you learn. New York: Hachette Book Group; 2013.

11. Côté J. The Development of Coaching Knowledge. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. 2006;1(3):217-222.

12. Olympiou A, Jowett S, Duda J. The Psychological Interface between the Coach-Created Motivational Climate and the Coach-Athlete Relationship in Team Sports. The Sport Psychologist. 2008;22(4):423-438.

13. Cockerill I. Solutions in sport psychology. Australia: Thomson Learning; 2002.

14. Weinberg R, Freysinger V, Mellano K, Brookhouse E. Building Mental Toughness: Perceptions of Sport Psychologists. The Sport Psychologist. 2016;30(3):231-241.

15. Jowett S, Cockerill I. Olympic medallists’ perspective of the althlete–coach relationship. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2003;4(4):313-331

16. Susie East f. Thirteen ways to think like a champion [Internet]. CNN. 2019 [cited 18 December 2019]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/08/03/health/psychology-of-winning-the-olympics/index.html