Featured

How the next decade can dislodge cricket's monopoly on Indian sports

I vividly remember the electrifying night of April 2, 2011, when more than a billion people plunged into collective euphoria and the whole of India resonated with a spiritous surge of patriotic pride. It was the night the Indian men’s cricket team won the ICC Cricket World Cup at the Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai, regaining the sport’s most prestigious trophy for the first time in 28 years. The eleven men who were responsible for the historic feet were serenaded everywhere, from the jam-packed streets to the hyperactive social media.

Five years later in 2016, an Indian team was crowned world champions again, this time in Ahmedabad. India’s kabaddi team had just won their third straight World Cup, but on this occasion, there was no countrywide explosion of delirious joy. In fact, most Indians (including myself at the time) were not even aware that India had won, or that there was a Kabaddi World Cup, or that Indians actually had a national Kabaddi team!

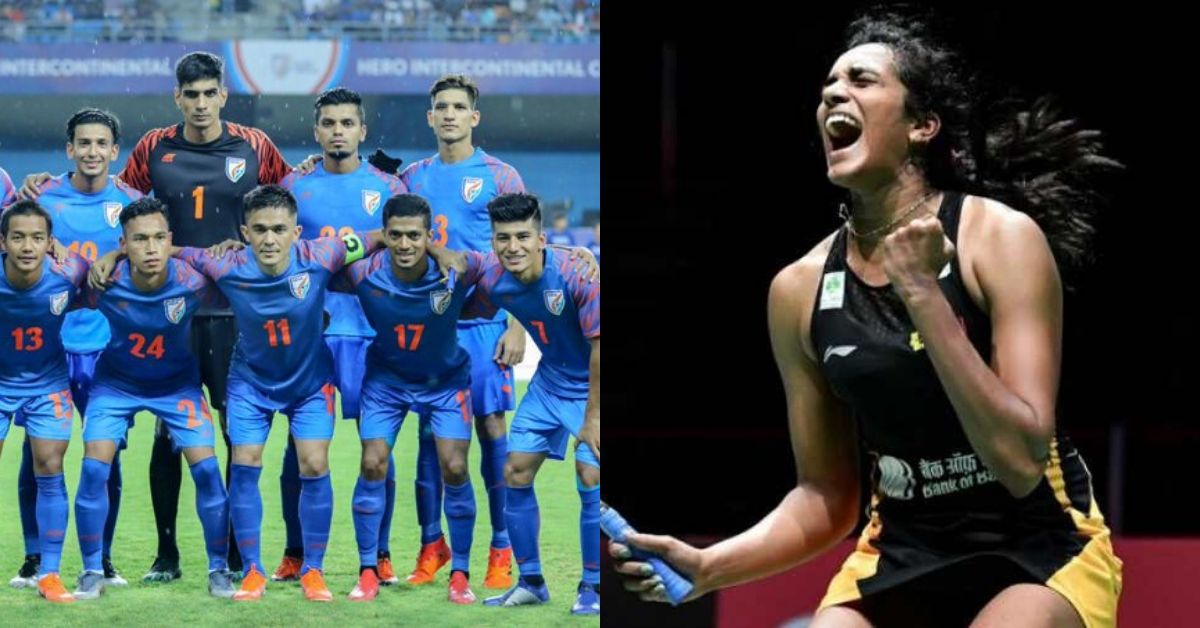

Welcome to India, the land of paradoxes and the spiritual home of cricket- a colonial relic that has transformed into a national obsession- which galloped along in the 2010s, broadening its claim over the epicentre of Indian sport. As a consequence, other sports were pushed further towards the periphery, producing a decade of action that saw cricket’s monopoly over fields and minds multiply several times over. The likes of badminton, football, hockey, and athletics had their fifteen minutes of fame (sometimes quite literally) at certain points of the decade before the limelight fixated once more on cricket (just the men in blue, though) and its fanatically idolised protagonists.

I have no problem with cricket leading India’s sporting identity; in many ways, it deserves to. But as a sports fan who has been pining for other games to receive due recognition in a nation endowed with talent, I am worried. My concern stems largely from the unprecedented commercialisation of cricket, as infrastructural and administrative lacunae and dwindling interest keep eroding other sports in the country. But with a new decade upon us and the accompanying hope that freshness brings, there is still a chance of lifting the rest of the best from their continuum of obscurity, so that they may jostle with the bat and ball to satisfy our sporting quotient.

Money matters

In 2018 (according to an India Times report), Indian cricket skipper Virat Kohli pocketed a salary that was ten times more than his Indian footballing counterpart, Sunil Chhetri, a man who has been (like Kohli) India’s most consistent player at the international level (and has more international goals than Lionel Messi). Nobody expects Chhetri- playing for one of football’s minnows in India- to have similar professional earnings as the most celebrated cricketer in the world. And yet, it is the extent of the gulf that is shocking, with the enormous deficit encapsulating the financial chasm that separates cricket from other sports in India, even for the elite performers.

If the 2020s are to herald any sort of meaningful change, the most important catalyst will have to be money. Today, a Yashasvi Jaiswal- who used to sell pani-puris for a living as an eleven-year-old- can become an instant millionaire courtesy the Indian Premier League auction (an event that alone enjoys more footage than many non-cricketing competitions combined), where he was bought for a whopping 2.4 crore rupees. Such incredible rags to riches tales are simply not feasible in other sports in India, and for most prodigious youngsters who dream of changing their lives by pursuing sports, cricket is their solitary option.

But how can funds in sports get distributed better across the field? The answer lies in starting at the top. The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) enjoys hundreds of crores of surplus every single year from the IPL alone and must do more to share its revenues for the welfare of other sports. Player salaries across the spectrum of Indian sports, as well as remunerations for coaches, trainers, and administrators, need to be increased if an adequate incentive is to be created to encourage the youth- especially from the less-privileged sections of the country- to make it big.

Also read: Skateboarding has found its place in Bengaluru

Into sight, into mind

Inextricably wound up with the finances of any sport is its visibility. Admittedly, this is a tougher area to handle, given the apparent lack of tangible measures that can be implemented. Inspired by the IPL, Indian football (through the Indian Super League) and kabaddi (through Pro Kabaddi) have replicated the formula of adding the stardust of celebrity to garner greater traction. But while the IPL can go from a Shah Rukh Khan somersaulting on the Eden Gardens turf to thousands of locals chanting for South African AB De Villiers in Bengaluru, the Pro Kabaddi League can only manage to shift from Amitabh Bachchan to…well, nobody in particular. The reason for this is the relative absence of the superstar culture in other sports, where only a few (like P. V. Sindhu or Abhinav Bindra) can shoot through to stardom.

But the superstar culture is not only cultivated on the field. In fact, a large part of it is fostered off it, through subtle forms of promotional packaging. For instance, the last few years have seen broadcast networks curate shows that not only provide match previews and analyses for hours on end whenever the Indian cricket team is in action but also devise more intimate content that offers a sneak-peak into the personal lives of cricketers besides tracing the team’s journey through semi-documentary style programming. Similar efforts can, of course, be made for other sports, but would people really want to know the ins and outs of hockey or athletics professionals? Despite the scepticism it might initially provoke, it is a gamble worth taking, for there are certainly profound narratives to be explored. As a country, we need more engaging material that highlights the stories of other sports in India, preferably without the glamour and glitter of Bollywood. After all, how many of us started following women’s wrestling and hockey in India after watching Dangal and Chak De! India?

Results count

Apart from injecting more money and air-time to propel the other sports forward, the third factor that can challenge cricket’s supremacy in the 2020s is something we, as fans, have little to no control over. It is the factor of performance, so often the be-all and end-all of all things sports. The burgeoning popularity of Indian cricket and the sustained dominance enjoyed by the national team (at least at home) is not a coincidence. While more attention would definitely help to resuscitate sports like kabaddi, better results are a prerequisite for a resurgence in most arenas like football, badminton, and hockey. A sensational outing for the Indian contingent at the Tokyo Olympics in 2020 could be the perfect launching pad for a decade of international sporting excellence, but such excellence usually requires patience, care, and nurture.

Laying the groundwork

The qualities required for consistent results are supposed to be harnessed by the infrastructural facilities at the disposal of sports authorities, which, in most cases, is in shambles in India. For my part, I have struggled to locate a decent football pitch that can be accessed without burning my pocket in my hometown of Kolkata, and unlike the hundreds of aspiring youngsters who kick, tackle, and slide in the mud-soaked grounds across the country, I only play for leisure.

Infrastructural improvements need to go hand-in-hand with legislation and campaigns on behalf of the government. One positive move that has made some inroads into a creating a holistic sporting culture is the Khelo India Youth Games- a national level multidisciplinary sporting initiative that began in 2018, but a whole lot more is required. If we cannot expect the likes of Sachin Tendulkar and Mary Kom to take a stand on social issues, the least they owe to the nation as Parliamentarians is a willingness to use their reach to promote more grass-roots sporting endeavours.

Cheer to change

However, when it is all said and done, breaking cricket’s stranglehold also boils down to the individual will of fans. If I shove my fingers through the air in an imaginary fist pump with my compatriots every time India wins a bilateral series in cricket, but simply let my thumb scroll over the news of Indians striking gold at an athletics world championship, I choose to remain enveloped in my cricketing cocoon. For other sports to come to the fore in the 2020s, cricketing acolytes have to learn to accommodate variety and diversity and show inquisitiveness beyond the 22 yards. Only then can India truly edge towards a more democratic playing field and the possibility of multiple collective outpourings of euphoria every year. After all, cheering for sports other than cricket in India will not be declared as anti-national anytime soon!