Asian Para Games

Para-sports should not just be noticed for medals: Sharath Gayakwad

In a country where most sports other than cricket get stepmotherly treatment, and badminton is perhaps one of the few sports to have properly entered the public consciousness, swimming is a far cry from people being aware.

And then, perhaps, comes para-swimming. At the most recently held Paralympics at Rio in 2016, India pulled in a tally of two gold medals, and one each of a silver and a bronze. The names Mariyappan Thangavelu and Devendra Jhajharia became well-known, if only for a short time. Perhaps in a few cases, they remained in consciousness. Deepa Malik won the silver in athletics and was felicitated for her win. But how many times do most spectators remember these names, as they should? How many times do we remember medal winners from ‘non-traditional’ sports beyond that 30-day gap?

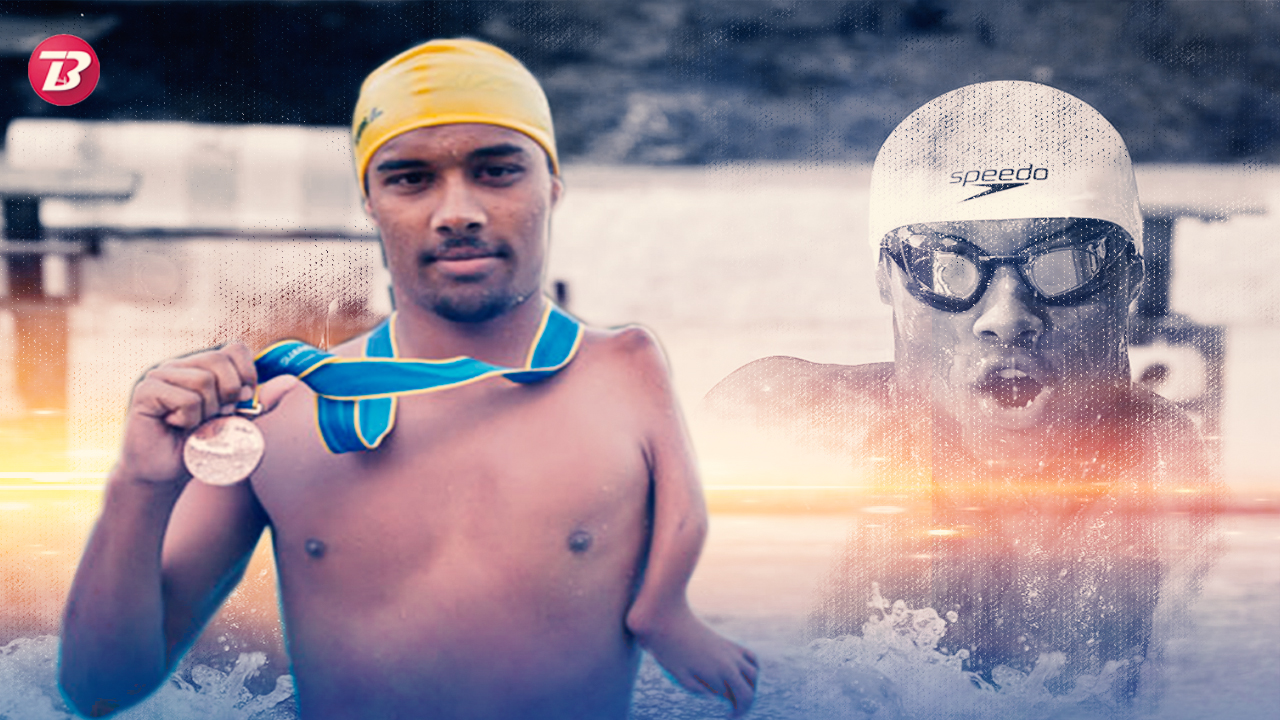

Enter Sharath Gayakwad. Now 27 and running his own academy, Gayakwad made the biggest splash, no pun intended, when he broke the record held by the iconic Indian athlete PT Usha: the record for most number of medals by an Indian at any multi-discipline event, winning a staggering six at the 2014 Asian Games.

With 30 international medals and 40 national ones under his belt, one would expect Sharath Gayakwad to be a household name. And still, perhaps, that biggest glory is not necessarily accorded to him.

But first, a look into Sharath’s history. The Bangalore-based champion started training early, and by 3 had already developed a keen interest in swimming. By 7 he was already training with his favourite ‘John Sir’ - the swimming coach John Christopher, with whom he has been associated until his retirement from professional swimming.

It has been a fruitful, happy, coach-student association and the two are friends today as well. But the coaching was not always smooth sailing. “John sir is an amazing coach,” Gayakwad says. “But there were no specialist para-coaches, and so John sir had to look up, learn new things, and then teach me. He figured out newer techniques and taught them to me"

"Finding specialist coaches for para-athletes is quite tough, and it is almost always the case that ‘regular’ coaches take on that mantle and many pick up skills and learn along the way how to train, and train with, a para-athlete.”

A coach and a mentor

It is the same “John Sir” who has been a pillar of support in the career of Gayakwad, both in terms of physical training and motivation. “There were so many times I wanted to quit, or just retire. But he kept my motivation going, and we kept swimming, and thats how the 2014 games happened.”

Image: ESPN

Image: ESPN One of those key moments came after the 2012 Paralympics in London.

“I was so demotivated, I was convinced I wanted to quit. I also had constant shoulder problems, and as a result of this, quitting was always at the back of my head at that time. I had decided, I’d been to the Olympics, Asian Games, that’s enough. But John Sir refused outright.”

“You have to swim,” he said. “He is one of my main motivations. With any other coach, I might have even gone ahead and quit the sport. But with him, I didn’t. I went on.”

Gayakwad has always had a passion for coaching. “Even when I was younger and still swimming full-time, I always wanted to coach someday,” he says. “Initially I thought when I quit early, I will take up coaching. So John sir told me, I should consider coaching but not at the cost of my career, so I did it part-time.”

Next came the asian Para-games in Guangzhou, South Korea. Sharath not only won medals, but also his career-highest ranking here. It was also then that he realised his passion for coaching was more than just a fleeting one. “I was not having fun swimming anymore,” he says. “Yes I am getting more sponsors than I used to, but is it fun, what happens if I stop swimming? Am I just swimming for money?”

Today, he coaches 70-80 kids and many of them are in the national arena. “I have so much pride in these kids,” says Gayakwad. “I love coaching. But there are of course things that full-time coaching brings - like logistics, back-end work, I didn’t necessarily think of that! Thankfully I have a great team that handles all this. Coaching is one of the things I was meant to do.”

On the perception of disability in India

“Sport has always been considered a volatile career,” says Gayakwad. Indeed, unless you are a cricketer or now, perhaps a tennis or badminton player, funding is not always consistent, and players bank on awards and ad revenues from the peak of their fame. There are highs and troughs and most athletes in these situations tend to bank on those highs - in terms of sponsorships and results, to coast through. Just as an example, Sharath quotes PV Sindhu. “When she kept winning big, and when she got silver at the Olympics, many raced to award her with cash prizes, she got many sponsorships, etc. But I think the money should come before, he says. Not after necessarily.”

Pointing out a key problem with the system, he says, “We race, in India, to inundate the athletes with cash prizes after they have won. After the fact is not when they receive their world-class facilities, nor when they need the money to train and to travel and for their sporting and daily expenses. We need to focus on nurturing the athlete before, so that they can become medal winners, rather than awarding them after they do.”

Indeed, support is neither ideal nor readily available, especially in a sport like swimming. “If the Federation gave support, they could do a lot,” says Gayakwad. However, right now, he avers, what they are doing is not enough. “Even if and when facilities do come in terms of support, they do not come at the right time and it’s the timing that is absolutely the most crucial aspect of training, tournaments and more.”

The system is broken: total apathy

Revealing the serious lapses in the system, Sharath reveals, “Even today, there is a lot of instances where we on’t know if we can attend the competition because the entries are done but the government has not cleared the team. Three days before departure, we were supposed to head Dubai for a tournament last year. THREE DAYS.”

The team received no intimation of their travel. In addition, sportsmen’s visas must be granted through the centre so there was really no avenue that they could have pursued independently.

According to Gayakwad, this was far from a one-time thing.

“This happens in 70% of the competitions we go for,” he says. “This is always the case. Whether the mistake is from the government or the federation, we don’t know. We don’t care whose mistake it is - it is the TEAM that needs the help. The mistake is there. The focus should be on training. But three days before we are due to travel, it is important that the kids are focused on their swimming, on their work, and not on worrying about travel and whether or not they will be able to participate. And that worry is always there, and it impacts them significantly. This has even happened in able-bodied sports.”

The federation, and those behind it, are also disorganised about national level athletes. “We made visa appointments in Delhi, our flight money, everything was done by us,” he says. “The government paid the visa fees, and that was it. Travel was all out of pocket. Despite repeatedly following up, we received no reimbursement.”

This is a constant issue with a system where, we have seen repeatedly, athletes are only awarded once they receive results - rather than being helped in any way possible to get the results. This is absolutely sub-par compared to other nations’ sporting prowess. “To compare, in the USA, if they have gone 3 steps, we’ve just taken the first. You need to provide the facilities. And if they are there, they are not encouraging. Some or the other issue always creeps up here.”

It is less of an problem, Gayakwad says, in private institutions. But even that “less of a problem” is glaringly bad. “In private institutions there is less of space to train, govt institutions the coaching quality is pathetic. Nutrition is not great, either.”

He cites the example of Great Britain. “They spent lots of money on training, coaching, nutrition, all aspects, and the cash awards given were comparatively little less. In india the training costs, the coaching, everything is minimal, and after winning a medal, the cash prizes are massive. But we don’t look at the athletes before they win and that’s the problem, or at least a large part of it,” Gayakwad says.

“PV Sindhu, she won an Olympic medal. Support was minimal before. After the games she is a multimillionaire, with ads, revenue, all of it as she deserves. But where was all that support when she needed it, rather than her and her family having to shell out of pocket to train in the first place?”

And whatever system still exists in place, is unsatisfactory, avers Gayakwad. ”The government has schemes but the process is very slow and the budget needs increasing very badly. Let us not heap prizes on people after they win - rather than looking at 1-2 medals in paralympics, let us look at giving them para-friendly facilities. Bringing in coaches who understand para-athletics. Bringing in tools and equipment and building faciltiies instead?”

To illustrate just how broken that system is, Gayakwad paints a vivid and true picture. “If you win gold at Olympics you get 1 crore,” he says. “But after the fact.”

“Now think of how far that 1 crore could have gone. That amount of money could’ve gone for four years with the maximum of facilities to train. Not just coaching but her racquets. Equipment. Travel expenses. These things add up significantly. Even coaching camps could have been included and they would still by far have been covered in the 1 crore.”

The system for retired athletes is no better, he says. “For those who have won for the country, you could receive a different combination or permutation of pension from the government. But it is definitely not enough to sustain a person, and most collect a pension in addition to working full-time on their own.”

“We need to, instead of heaping glories and awards and money on athletes only after they win, heap money and glories on them as they train. Provide them with the facilities they need to win. That way you create more medalists to celebrate as well.”

The state of para-athletics today:

“It is after getting a medal that they noticed. If a para athlete hadn’t won a medal at Rio, para-sports would’ve been in a really bad place. In 2016 we got two gold one silver one bronze, para sports would’ve otherwise completely dropped off the radar of public awareness,” he says.

“It is always abut the medals but it shouldn’t be noticed just because they are winning. It should be about how to develop the sport – how to get medals from the sport and not celebrating those which come by chance."

How can making para sports a priority change?

“Well, there’s still a huge lack of knowledge about para sports, says Sharath. “They still think, oh, there’s a lot of disabled people around, some of them are competing, okay sure.”

The USA has training courses that, Sharath says, account for disabilities.

India needs something like that.

“As an able bodied coach they have systems, and those are fairly effective. But there is absolutely no education on para-courses, and many coaches - like my own John sir, have to pick it up as they go along, and learn on their own. Teaching and sensitization here would go a long way.”

“There are 400-500 people for the national championships, 500 best of the best kids. In Karnataka,there are about 50-60 swimmers for the state championships, and 40 heading to the nationals. There are about 1000 differently abled swimmers in India today. Not all have coaches who know para swimming or understand it completely. And there you can see the problem.”

This problem goes to the roots and then affects the entirety of the sport. “Maybe the para athletes continue without being discouraged, but the officials don’t understand the importance of facilities, etc; if my coach knew or had that kind of education before, I would have achieved a lot more. And that’s true of many athletes. Even today, more than a decade later, many are still going through the issues which I did,” he says.

Gayakwad takes the mantle seriously. ”For me it’s a responsibility . My goal is to coach them. For the 2018 Asian para games I have TWO swimmers who are hopeful to take part in the Asian para games.”

How can external help help? “It doesn’t *HAVE* to be coaching. Can be anything to develop the sport. A bunch did sports medicine. It doesn’t have to be that you have to train their kids. One kid is taking up nutrition as a degree. Their roles can be in administration as well.”

How to fix the problem

Corporate-social responsibility is a big avenue, Gayakwad says. But the rot needs to be combatted from within. “Each state can get a senior sportsperson educated enough to have the willingness to contribute to the sport and develop the sport in the country, and If they can get Youth Min. Fix the problem from the inside out,” he says.

"There are one thousand steps to do it and all need to be done in time. But it is bureaucracy, and not everyone along the lines understands sports. Therein lies such a big part of the issue.”

I don’t believe in awards. Getting an award is a govt representation or respect I never worked towards “AWARDS”. The swimming is the goal. Not the awards.

But even then, Gayakwad says, the problem lies within. Within the funding, which is slow but lately, he says, is at least better than it was over a decade ago. The facilities need to improve. The funding needs to improve. Maybe then, as Sharath suggests, we will promote and encourage people to win medals, rather than celebrating when, by chance, they do, of their own skill and accord.

The system, in all sport, needs to change from inside out; and rather than just cosmetic changes, every step needs to change. Whether that takes one year or ten, it is what will truly win us tournaments. Maybe then, India will have more athletes to celebrate, equally.