Badminton

BWF’s revamped tour, India’s shrinking footprint: What changed and why it matters - Explained

In BWF’s revamped 2027–2030 calendar, Syed Modi International is downgraded and two Indian events are dropped, shrinking India’s presence on the global badminton tour.

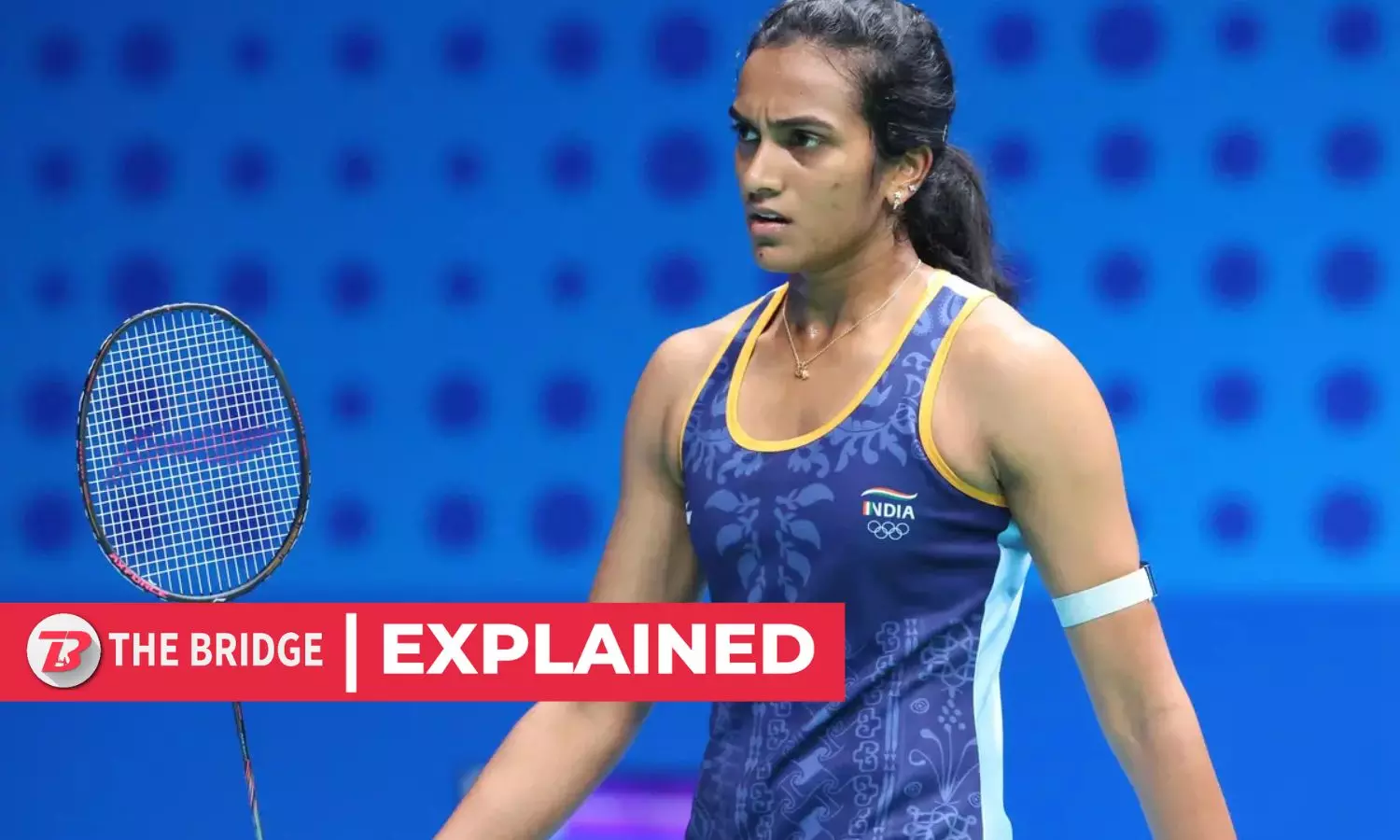

BWF’s new tour, India’s shrinking footprint: What changed and why it matters - Explained (Photo credit: Paris Olympics)

The Badminton World Federation (BWF) unveiled a sweeping overhaul of its World Tour and major championships for the 2027–2030 cycle. The headline changes speak of growth, visibility and player welfare. For India, however, the announcement carries a far more complicated subtext, one that blends relief, loss and unanswered questions.

At one end of the spectrum is stability. The India Open (badminton) will continue as a Super 750 event, preserving its place among the sport’s elite tournaments despite criticism from players this season over issues such as venue conditions and tournament operations.

At the other end is a clear downgrade.

Syed Modi International to Super 100

The Syed Modi International, a long-standing fixture on the Indian circuit, has been pushed down from Super 300 to Super 100, the lowest tier on the BWF World Tour. Two other international tournaments previously staged in Guwahati and Odisha have been removed from the calendar entirely. From hosting four BWF events, India will now host only two.

The India Open, which itself came under public scrutiny this year after players complained about cleanliness and facilities, has emerged untouched in status.

The changes arrive at a moment when the BWF is attempting to redefine what top-level badminton should look like over the next decade.

From 2027 onwards, the World Tour will be rebuilt into a 36-tournament circuit across six levels, including the creation of five Super 1000 events, the highest tier of regular tour competition. Across all levels, the annual prize pool will rise to around USD 26.9 million, with increases promised for every category, from Super 1000 to Super 100.

But the most consequential shift is not financial. It is structural.

Format changes in Super 1000

BWF has decided to increase the numbers of Super1000 events - The top tier of World Tour - from 4 to 5, with the Denmark Open now upgrading from Super 750 to Super 1000 event, starting from 2027.

The Super 1000 tournaments will move to an 11-day format spread across two weekends, introducing group stages in singles before the knockout rounds. Doubles events will continue with knockout draws. For the BWF, this is about reducing the brutal consequences of early exits after long-haul travel, while guaranteeing players more court time and visibility.

It is a format change that echoes long-standing demands from players, including former world number one Viktor Axelsen, who has repeatedly called for reforms to workload, scheduling and tour structure.

The new system is designed to ensure that players are not eliminated after just one match and one bad day. It also gives broadcasters a longer, more predictable window of elite competition, a key commercial consideration in a crowded global sports market.

The reform agenda goes well beyond the weekly tour.

The BWF World Championships will also move to a group-stage followed by knockout format, ensuring that every player competes in at least two matches, mirroring the Olympic model. Meanwhile, major team events such as the Sudirman Cup and the Thomas and Uber Cup Finals will be expanded to include more nations, increasing international representation and competitive diversity.

Boost in visibility

Behind the scenes, the engine driving this transformation is visibility.

From 2027, the number of TV-produced badminton matches is expected to almost double, from roughly 1,410 to around 3,000 matches per year. Every match at Super 1000 tournaments will be broadcast globally, addressing a long-standing frustration among players and fans over untelevised side courts and inconsistent production standards.

This broadcast expansion is underpinned by the BWF’s extended commercial and media partnership with Infront, which runs until 2034 and is central to the federation’s ambition of repositioning badminton as a premium global entertainment product.

For the BWF, the logic is clear. Longer events, more matches on television, more consistent storytelling around players and better scheduling conditions are meant to elevate the sport’s commercial value while making professional careers more sustainable.

For host nations, however, the new world comes with sharper competition.

As the tour becomes more concentrated around premium, high-production events, the margin for countries hosting mid-tier tournaments becomes thinner. Super 300 and Super 100 events are increasingly expected to align with stricter commercial, broadcast and presentation standards, not just sporting ones.

It is in this context that India’s reduction on the hosting map becomes significant.

The downgrade of the Syed Modi International is not simply a fall in ranking. It affects the level of players likely to attend, the ranking points on offer, the global broadcast footprint and, ultimately, the visibility of Indian badminton at home. For domestic players, Super 300 tournaments on home soil have historically provided valuable opportunities to collect points without the burden of overseas travel. A Super 100 event offers far less of that competitive leverage.

Equally important is what the announcement does not clarify.

The BWF has not indicated whether operational standards, commercial performance, venue infrastructure, broadcast readiness or strategic market considerations played a role in deciding which Indian tournaments were retained, downgraded or removed. Without transparency, the message to national federations and local organisers remains ambiguous: improve what, exactly, and to whose benchmarks?

What is unmistakable, though, is that the global tour is being reshaped around fewer, bigger and more television-driven events.

In that world, the India Open’s retention as a Super 750 tournament becomes a protective anchor for Indian badminton, a guarantee of continued elite exposure in New Delhi. But the shrinking of the broader hosting footprint signals a narrowing of India’s role as a regular stage for the world’s top players.

The new BWF calendar promises more matches, more cameras, more prize money and a more polished global product. For players, it could genuinely mean fairer schedules and longer careers.