Law in Sports

Betting and Gambling Report: The Law Commission of India Hedges its Bets and Still Loses

In early July 2018, we saw a spate of headlines and news reports stating that the Law Commission of India (the Commission) had recommended that betting and gambling be legalised in India.

These arose from the release of the Commission’s 276th Report, titled Legal Framework: Gambling and Sports Betting Including in Cricket in India (the Report), prepared by the Commission pursuant to the Supreme Court of India’s reference in the case of Board of Control for Cricket in India v. Cricket Association of Bihar & Ors. (Civil Appeal No. 4235 OF 2014).

In the BCCI case, the Supreme Court was considering the recommendations of the Supreme Court appointed Justice R.M. Lodha Committee in its ‘Report on Cricket Reforms’, wherein the Committee suggested that legalising sports betting could help reduce sporting fraud and curtail the influence of unethical elements on the sport and its participants.

From this, arose the Supreme Court’s reference to the Commission to examine the issue of legalising betting in India. While it was only asked to examine the issue of sports betting, the Report addresses betting as well as other forms of gambling, as the Commission reasoned that these are closely associated, and considering one without the other would render the exercise incomplete.

What followed the extensive publicity for the Report was a quite remarkable Press Note issued by the Commission the very next day, seeking to clarify its position that it had not recommended legalising betting and gambling and, quite to the contrary, had categorically recommended that these practices remain totally banned.

Regulation rather than prohibition

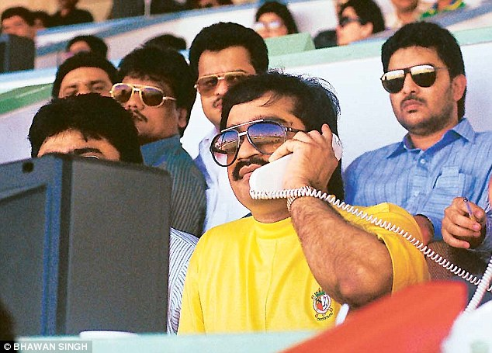

It has long been believed that the underworld has deep connections to the betting and gambling markets in India with the D-Company of Dawood Ibrahim often coming up in related conversations. (Image: Hindustan Times)

It has long been believed that the underworld has deep connections to the betting and gambling markets in India with the D-Company of Dawood Ibrahim often coming up in related conversations. (Image: Hindustan Times) It wished to clarify that its Report on proposed regulatory measures and mechanisms was apparently only in the scenario wherein betting and gambling were legalised given that regulation rather than prohibition remains the only viable option.

Reading the Report carefully, there in indeed one paragraph where the Commission states that it has reached the “inescapable conclusion” that legalising betting and gambling is not desirable in India in the present scenario (which includes the current socio-economic atmosphere and social and moral values). However, in the very next paragraph it hedges its position, stating that notwithstanding its views, regulation rather than prohibition remains the only option, given the “incapability” of enforcing a complete ban.

This more or less annuls its socio-economic and moralistic position on a ban and vice versa. It is worth asking what the value of a recommendation is if it is incapable of enforcement. Similarly, is it worth writing a 145-page Report outlining measures and mechanisms to regulate, when that is not the “inescapable” position you wish to espouse? This dichotomy finds its way into the essence of the Report, its recommendations and positions and unfortunately completely devalues the Commission’s research exercise.

It is worth asking what the value of a recommendation is if it is incapable of enforcement.

First, the Commission takes the aforementioned social and moral high ground backing prohibition. In stating that a complete ban is incapable of being enforced, it is unclear how it has reached this conclusion.

Does it believe that it is impossible to enforce a total ban?

That it is too expensive to do so?

That this quest both currently and potentially lacks political and administrative will, given the state of India’s polity?

The answer is both important and missing from the Report.

In stating that regulation rather than a ban is the only viable option, the more charitable view is that a complete ban is inherently capable of enforcement but this is laid bare by the fact that a number of jurisdictions effectively police absolute bans.

Is it worth writing a 145-page Report outlining measures and mechanisms to regulate, when that is not the “inescapable” position you wish to espouse?

Is it worth writing a 145-page Report outlining measures and mechanisms to regulate, when that is not the “inescapable” position you wish to espouse? In that light, one could only see the Commission’s conclusion as a damning indictment on the Indian state’s policing capabilities and priorities in general and its relationship with the betting and gambling industry in specific.

Next, the inherent socio-economic and moral conundrum is furthered when the Commission, while providing a laundry list of “safeguards” required alongside the “inevitable” legalisation of betting and gambling, also lists the potential positive impact that this will have.

If one believes these acts are morally wrong and inappropriate for India’s economic and social standing, it is unclear how it might be relevant that there will be additional revenue for the state, that sports fraud can be monitored or, for that matter, a bizarre reference made by the Commission that the Mahabharata would have had a different script in a counterfactual world?

If the inevitability is due to a lack of choice or ability to enforce a total ban, the (theoretically) positive externalities are irrelevant and one must just get down to business and put in an effective regulatory system. There is no need to justify the shift from a ban to regulation because we get to this point as a result of a non-choice and not because of these benefits. While staying on the moral point, the Report also does not look at the potential negative impact this can have on the national and personal moral and normative structure.

If one believes these acts are morally wrong and inappropriate for India’s economic and social standing, it is unclear how it might be relevant that there will be additional revenue for the state

While it does seek to protect the poor by limiting them to small gambling rather than proper gambling (the Commission’s own words) and stopping them from spending their government subsidies, it does not explore the impact of legalising betting and gambling on the illegal market and player behaviour and conduct. While unlicensed gambling would remain a crime, it would move from a category of an offence involving “moral turpitude” to a more benign “licensing violation”. The impact and costs of this shift remain unexplored.

Impact and cost questions remain unanswered in Report

Perhaps most importantly, it is unclear how the Commission sees the regulatory structure it proposes as capable of solving the illegal betting and gambling problem. Among its recommendations are included making all betting and gambling cashless and regulated by a game licensing authority, the limitation of “proper gambling” to members of higher income groups, the requirement of PAN and Aadhar numbers in order to participate, a cap on monthly/annual/periodical betting/gambling transactions per person and restricting individuals living below the poverty line and recipients of government subsidies and similar vulnerable sections from participation.

This, quite obviously, leaves many holes and supply gaps that the illegal betting and gambling market will continue to readily fill. Further, if the complete ban is incapable of enforcement, will this licensing structure be any different when it comes to non-compliant actors? If you cannot enforce a ban can you enforce a licensing structure? Does this simply come down to an attempt to co-opt a part of the market for revenue considerations and then (continue to) throw up our hands on the illegal market?

The Commission is purely an advisory body to the Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India and its recommendations are not binding on the Central Government. The issue of the legality of betting and gambling in India is not an easy one. There are many layers to the debate.

In approaching the subject matter with a mix of confusion and despondency, the Commission has fallen into a trap which devalues its recommendations. Both the subject matter and the national debate deserve better.

Also read: What the elections held after five years mean to DDCA